2. RMMV Approaches and Tools - an Overview

This Section describes how RMMV approaches, and tools, including data sources are classified. Although one may immediately think of technology when considering RMMV, the success of RMMV approaches depends on involving the right people and planning the right courses of action. Projects using RMMV can be implemented without special technology, but only with good routines, good management, and the involvement of substitute actors.

RMMV approaches can be classified as either institutional approaches or as using technical tools and additional data sources. Institutional approaches are defined by the setup and roles and responsibilities of project stakeholders to ensure effective management, monitoring, and verification of projects. They are crucial for interaction with others, especially if qualitative data needs to be collected. Technical tools are defined by the technology used. They ease or enable the collection, transmission, aggregation, structuring, management, analysis, verification, visualization, and interpretation of information. Technical tools may support local staff (e.g., supporting an enumerator with a survey app) but may also be used to collect information from independent data sources (e.g., satellite data) or manage several types of information from various sources (e.g., (Remote) Management Information Systems). Overall, an appropriate mix between institutional approaches, technical tools, and data sources needs to be chosen for each project.

2.1 Institutional Approaches

2.1.1 General Description of the Institutional RMMV Approaches

When deciding on which institutional approach(es) to use, the underlying question is always who will take over the specific responsibility of monitoring or verifying project data if international project staff (Remote Monitoring) or international KfW staff (Remote Verification) cannot access the project sites?

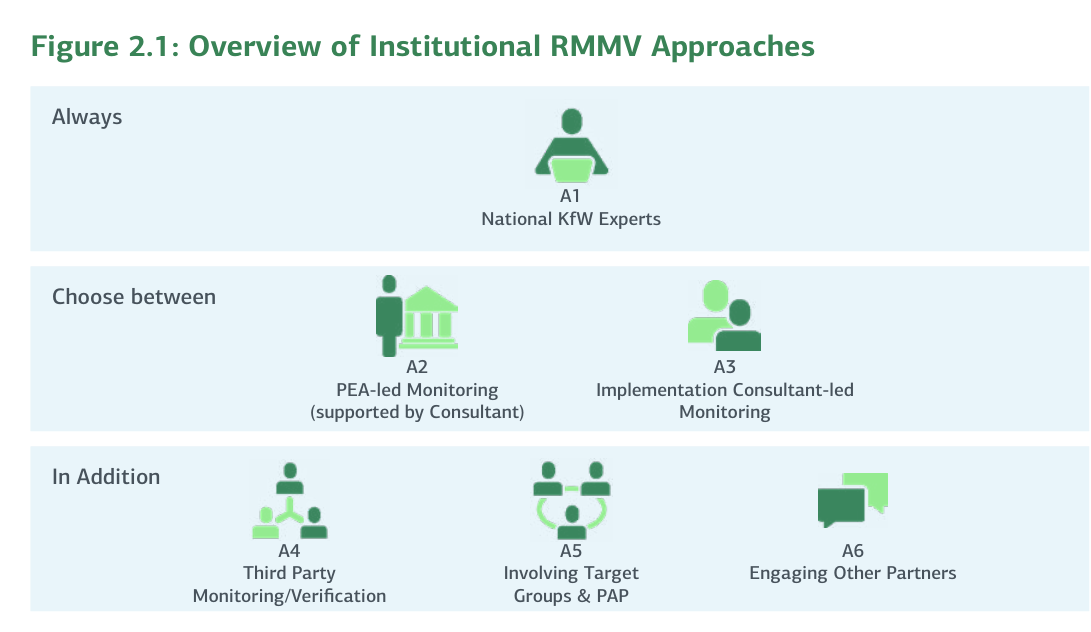

KfW has categorized institutional approaches for RMMV as follows:

Figure 2.1: Overview of Institutional RMMV Approaches

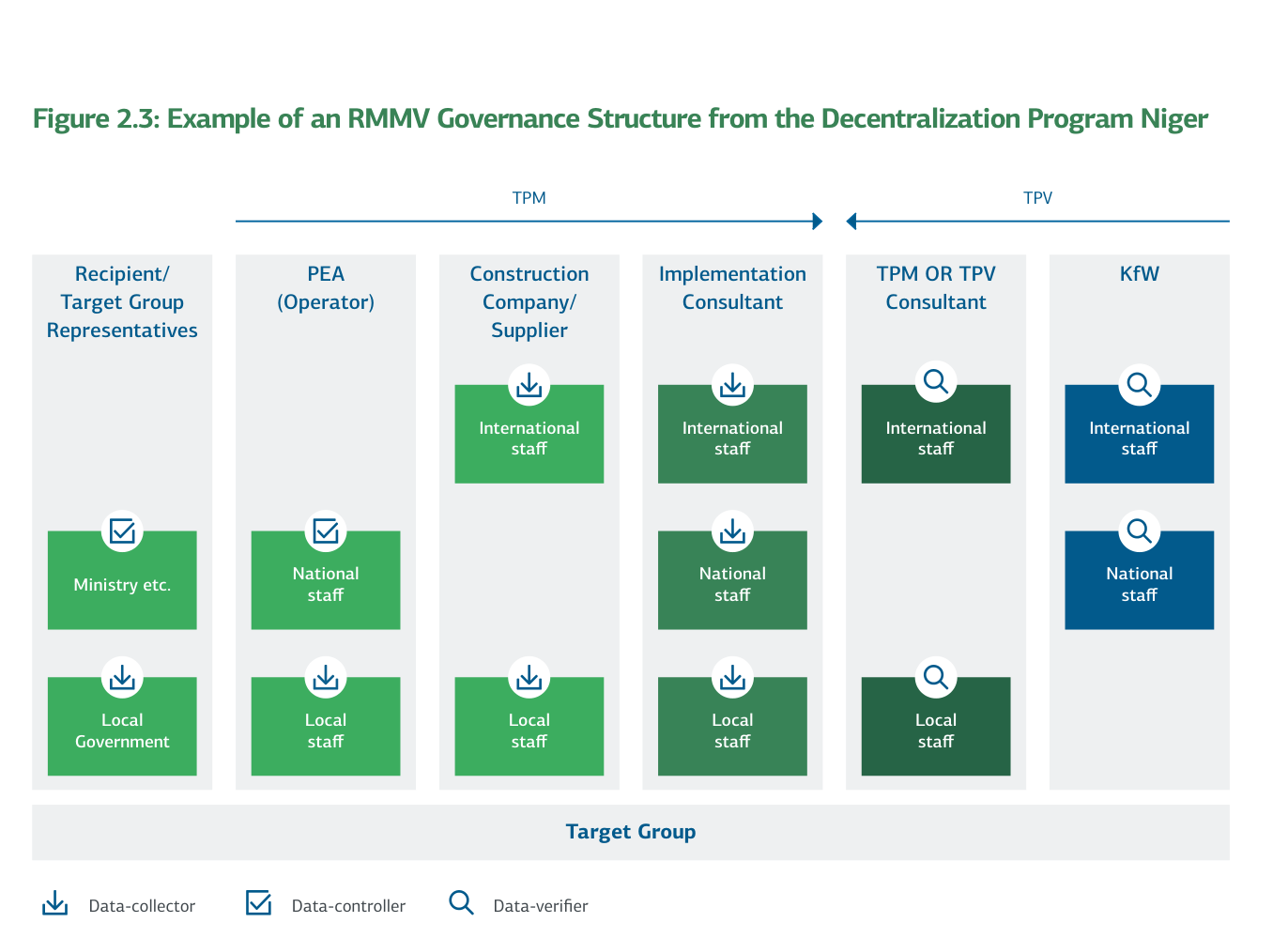

In KfW's experience, the type of institutional RMMV approach used depends on the structure, resources, and capacity of the Project Executing Agency (PEA). Table 2.1 provides an overview. Institutional RMMV approaches cover all stages of the project cycle; this will be further explored in Section 3 RMMV within the FC Project Cycle.

Table 2.1: Overview of Institutional RMMV Approaches by PEA Capacity

| Use | PEA with strong capacities/sufficient resources | PEA with limited capacity/insufficient resources or No PEA |

|---|---|---|

| Always recommended when using RMMV | Increased Responsibility for National KfW Experts in Remote Verification (A1) | Increased Responsibility for National KfW Experts in Remote Verification (A1) |

| Always choose either A2 or A3 as your main institutional RMMV approach | PEA-led Monitoring: Monitoring by PEA staff (A2) | PEA-led Monitoring: PEA staff supported by an Implementation Consultant (A2) Consultant-led Monitoring: Implementation Consultant with increased local capacities (A3) |

| Additional institutional approaches (in addition to A2 OR A3) | Third-Party Monitoring (as part of the project) or Third-Party Verification (commissioned directly by KfW) (A4) Involving Target Groups and Project-Affected Persons (PAP) (A5) | Involving Target Groups and Project-Affected Persons (PAP) (A5) Engaging Other Partners (A6) |

Note: Institutional RMMV approaches are designated with a code from A1 to A6.

A1 Increased Responsibility for National KfW Experts (Default Remote Verification Approach)

Providing KfW national experts with increased responsibility for verifying important information related to the project throughout the project cycle is always an excellent way to fulfill KfW's verification duties wherever KfW can rely on country offices or satellite offices, and security risks are not too high. The KfW office in Pakistan has, for instance, hired a national technical hydropower expert who is taking over some of the verification tasks that are usually part of the KfW headquarters-based international technical expert's duties, under their technical supervision. National KfW experts may also take on increasing responsibility in coordination and interaction with the PEA, as agreed with the KfW PM. This requires an adaptation of the national expert's job description in terms of qualifications and tasks. This change in responsibility often implies a higher workload for national and technical KfW experts and their inclusion into more KfW portfolio management procedures, such as the new collaboration model. For this purpose, KfW national experts need to have access to a wider range of training courses and coaching from PMs and technical experts, including training on RMMV, digitalization, and other important topics like participatory M&E approaches or geospatial tools and data sources.

A2 PEA-led Monitoring: PEA Staff Supported, in Most Cases, by an Implementation Consultant to Conduct the Remote Monitoring and/or Remote Management of the Project (FC Default Institutional Monitoring Setup)

In this default (i.e., most frequent) scenario, the PEA leads (Remote) Monitoring via its own staff, frequently with support from an international Implementation Consultant or a consulting consortium. In some projects, the PEA's staff take the lead in (Remote) Monitoring. This is the case when the PEA is a strong partner and experienced in German Financial Cooperation projects (government entity, public company) or is a UN agency or non-governmental organization (NGO). Often, the PEA is supported by the international and national staff of an Implementation Consultant, who strengthens the PEA's monitoring capacity, immediately checks the PEA's reporting, supports data cleaning, and assures monitoring quality.

A2 Special Case: Main Modalities of KfW Cooperating with NGOs as PEAs

In fragile contexts, KfW often partners with NGOs who take over the role of the PEA. Since RMMV is most frequently applied in these environments, the main modalities of such collaborations are highlighted below:

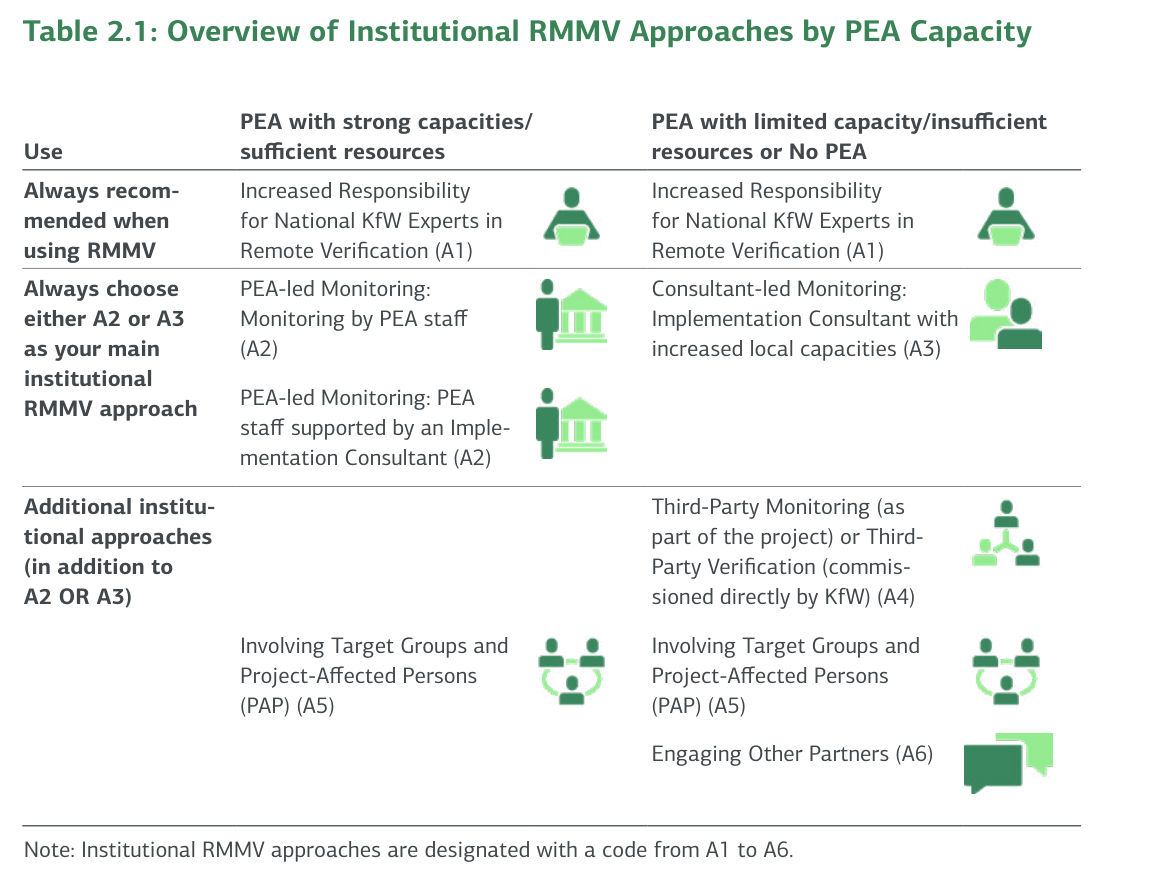

Cooperation between KfW and an NGO can be either based on a direct contractual agreement between KfW and the NGO or on an indirect contractual agreement that requires further parties in the contractual concept:

Figure 2.2: Main Modalities of KfW Cooperating with NGOs

-

Direct Contract KfW & NGO: KfW and the NGO have a direct contractual agreement and the NGO is both the direct contract partner of the Grant and Separate Agreement. In this case, the NGO is both recipient of the funds and the PEA and is selected by KfW through appraisal.

-

Indirect Relationship: The recipient of the funds is the partner country with whom KfW concludes the Grant Agreement, while the NGO holds the role of PEA. The Separate Agreement is concluded by KfW and the NGO. Beyond that, the NGO is also contractually linked to the partner country by a channeling agreement.

-

Indirect Nature: The cooperation between the NGO and KfW can also be of an indirect nature and does not need to be based on direct contracts between the two. In this case, both the Grant and the Separate Agreement are concluded by KfW with the partner country or an UN organization who then conclude a separate contract with the NGO acting as a service provider.

-

Fund/Foundation Model: KfW concludes direct contracts (Grant Agreements and Separate Agreements) with a fund/foundation or UN organization that subcontracts to many NGOs.

A2 Special Case: Main Modalities of KfW Cooperating with UN Agencies as PEAs

In fragile contexts, especially, UN agencies are often chosen as the PEA and Project Implementing Agency. A full accounting audit of the use of funds is generally not possible as UN agencies usually apply the single audit principle. International Public Sector Accounting Standards are applied. The respective UN agency is thus responsible for the correct use of funds during the entire project, including the funding of potential subcontractors or NGOs. Certified and uncertified financial statements are provided. This reduces KfW's requirements for Remote Verification. However, regular physical audits of the use of funds by KfW are practiced.

A3 Implementation Consultant-led Monitoring: Consultant with Increased Local Capacities for Remote Monitoring and/or Remote Management (Alternative Institutional Monitoring Setup-up to A2)

A consultant-led monitoring approach can be used at different stages of the project cycle: during preparation for conducting Feasibility Studies (when there is no designated PEA yet) and ex-post evaluations (after the PEA has already completed the project), and during implementation as Implementation Consultants or monitoring consultants. In fragile countries, Implementation Consultants may take over extensive responsibilities from the PEA and may even act as a de facto PEA, executing the entire project. This may be the case, if there is no capable PEA for the envisaged project type or if the mandated PEA has very limited capacities. Also, international consultants are sometimes in a better position to conduct monitoring by increasing their local staff capacities.

Additional institutional RMMV approaches:

A4 (Remote) Third-Party Monitoring or Verification (in Addition to Other Institutional Approaches)

Third-party monitoring (TPM) or verification (TPV) is conducted by an international or national TPM consulting firm that is contracted more or less independently of the PEA and Implementation Consultant during the implementation of a project. The goal is to complement and/or verify monitoring information gathered by the PEA and/or Implementation Consultant to ensure that the project is executed in line with agreed procedures and is headed toward the agreed objectives. Unlike Implementation Consultants, information collected by TPM Consultants is not (only) automatically integrated into the PEA's data systems but is (also) directly communicated to KfW.

A5 Involving Target Groups and PAP (for Remote Monitoring and/or Remote Verification, in Addition to Other Institutional Approaches)

Participatory approaches can be used throughout the project cycle-for example, during the project design, selection of measures, location, infrastructure design, outcome monitoring, and impact evaluations. In contexts of fragile and conflict-affected states, as well as in cases with social and environmental risks, participatory approaches are particularly important to ensure the conflict sensitivity of the project and the application of the do-no-harm principle.

Target groups usually have a strong intrinsic interest in monitoring. Involving a defined target group through different methods may help generate valuable ideas and feedback during project preparation, implementation, and operation. Methods range from telephone interviews, focus group discussions, panels for representative surveys, fuzzy cognitive maps, social network analysis, topic modeling, interactive radio shows, and micro-narratives to community-led monitoring and mapping, such as participatory statistics and participatory rural appraisals (PRA), community-based participatory research (CBPR), and participatory action research (PAR), or financial participatory approaches (FPA) sometimes combined with e-participation and crowdsourcing.

A6 Engaging Other Partners (for Remote Verification in Addition to Other Institutional Approaches)

Engaging (other) government entities, development partners, NGOs, and research institutes may also support Remote Monitoring and Verification. These actors frequently have access to areas inaccessible to international development staff and may perform basic output monitoring (like a TPM Consultant) or generate other project-relevant data.

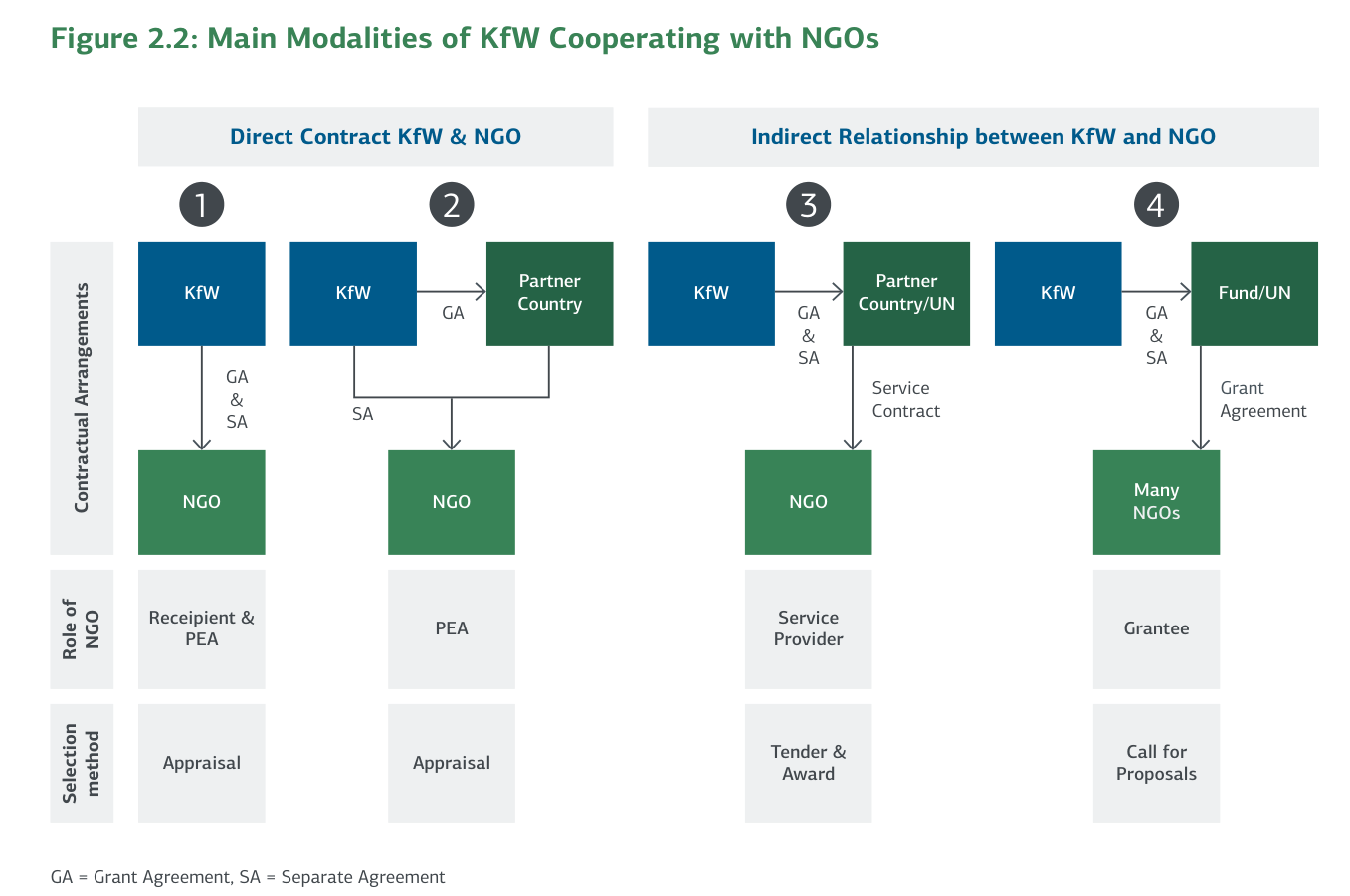

2.1.2 Institutional Setup and Changing Stakeholder Roles in RMMV

An appropriate institutional setup based on a solid project governance structure is crucial for successful Remote Management, Monitoring, and Verification. It enables the triangulation of data and verification. When developing the project setup and the institutional RMMV approach, the roles, interests, and functions of the stakeholders need to be considered.

In a monitoring setup, one can distinguish three roles:

- Controller of the data/tool: controls (and/or owns) the tool (if existent), evaluates and processes data, ensures data quality

- Monitoring agent/data collector: gathers data in the field (e.g., during site supervision)

- Data verifier: verifies and triangulates data

Figure 2.3: Example of an RMMV Governance Structure from the Decentralization Program Niger

Although the roles of various stakeholders may differ in each project, the following observations regarding the changing of certain roles and the resulting issues and potential conflicts of interest can be made:

-

Direct data access by KfW: KfW may receive direct remote access to project data for verification purposes, which is usually not the case in a project that does not use RMMV.

-

KfW national experts may have increasing responsibility: If international KfW PMs and technical experts cannot travel to the target area, the role of KfW national experts in interaction with the PEA may increase.

-

Changing role of the PEA: Project executing agencies (PEA) remain data controllers, collectors, and users. The PEA may view an RMMV setting as an opportunity to execute the project(s) more independently.

-

Changing role of the Implementation Consultant: The Implementation Consultant's role changes in a similar fashion to the PEA's role.

-

Third-Party Monitoring (TPM) Consultant: A new actor that plays an important role as a verifier/triangulator of data provided by the PEA.

-

Target groups: May play a more active role in data collection since they directly benefit from the services provided.

2.1.3 Possible Conflicts Between Actors and Conflicts of Interest

Changing the roles of the stakeholders may heighten tensions or lead to new types of conflicts. This section will present challenges that can occur when roles are changed and describe how they can be prevented or mitigated.

PEA and KfW (A2)

The PEA may not accept Remote Verification by KfW. PEAs may not be comfortable with the different or heightened involvement of KfW in controlling the project and may even resist it. Therefore, if this is considered a risk, KfW should introduce RMMV approaches early and make them a requirement for implementing projects.

Some PEAs may resist the introduction of technology-based automated data sharing, e.g., through a Remote Management Information System (R/MIS), Building Information Modeling (BIM), or data-sharing room. If KfW receives instant access to low-level disaggregated data, the PEA may feel tightly controlled.

PEA and Implementation Consultant (A2 and A3)

The potential conflict between the PEA and the Implementation Consultant about what is being reported may be enhanced. If external verification is weak, PEAs may be tempted to underreport problems encountered during implementation.

PEA and TPM Consultant (A2 and A4)

Tensions between the PEA and TPM Consultant may arise if they have different opinions, particularly about the deficiencies of a project. The PEA may feel that it is being criticized without a full understanding of the particular history and context of a project.

2.1.4 Creating an Incentive Model for Truthful Project Reporting

Incentives can help ensure correct, good quality reporting that addresses all important aspects of the project, including the risks and challenges. These three examples illustrate this point:

-

The consultant may be incentivized to ensure adequate data quality: If verification by KfW and ex-post evaluations depend on the quality of data, especially GPS data, the accuracy of this data is crucial and should be the consultant's responsibility.

-

Municipalities may be incentivized to use a citizen feedback-loop system: Performance-based donor-funding of local community development can create a positive incentive for governments to allow greater citizen scrutiny and participation.

-

Citizens may need to be incentivized to participate in a citizen feedback-loop system: In some approaches, citizens receive a small benefit for their active participation in monitoring, especially if they are not directly benefitting from a project.

2.2 Technical Tools and Data Sources

2.2.1 Overview of Technical Tool Types

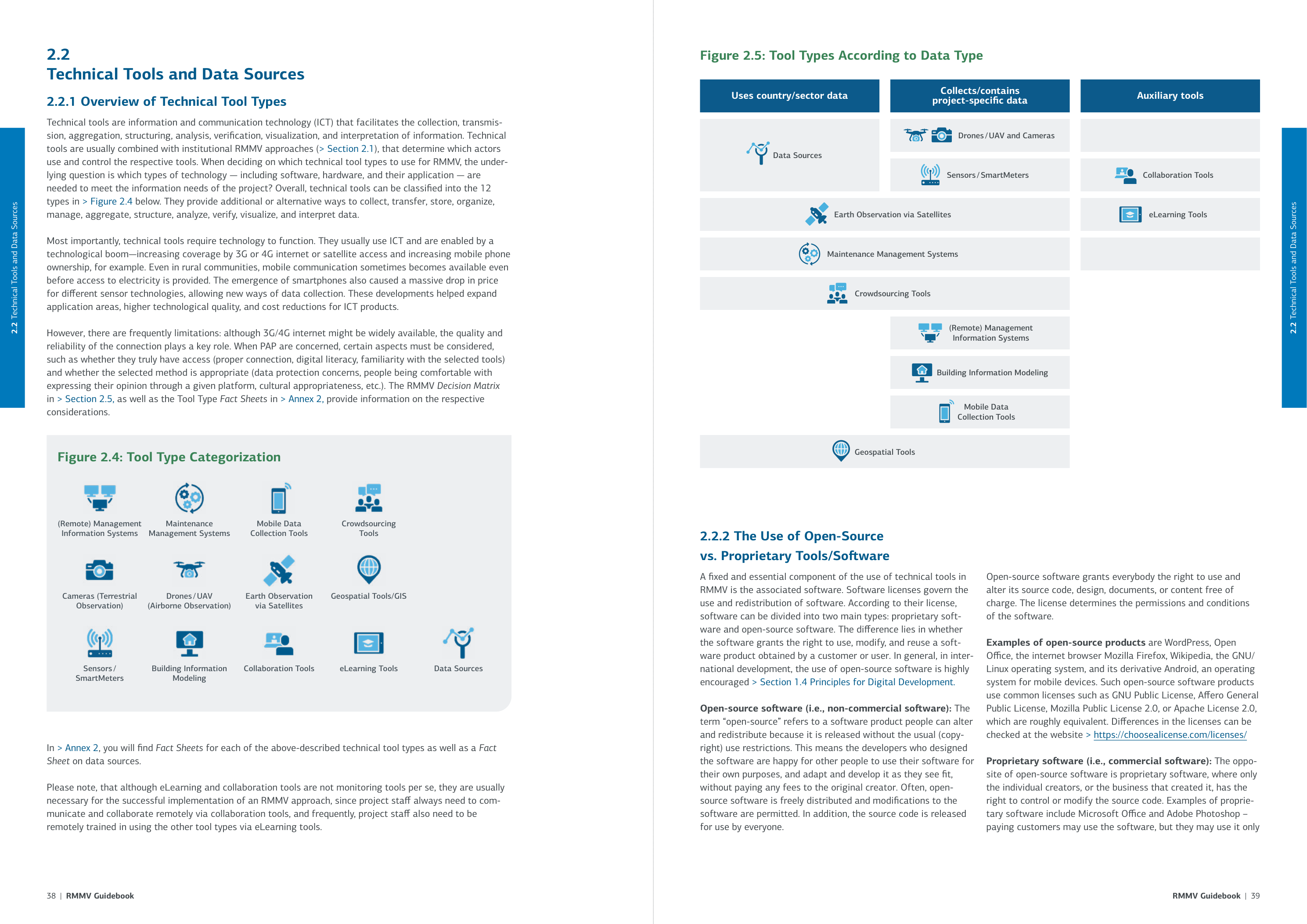

Technical tools are information and communication technology (ICT) that facilitates the collection, transmission, aggregation, structuring, analysis, verification, visualization, and interpretation of information. Technical tools are usually combined with institutional RMMV approaches that determine which actors use and control the respective tools. When deciding on which technical tool types to use for RMMV, the underlying question is which types of technology - including software, hardware, and their application - are needed to meet the information needs of the project?

Overall, technical tools can be classified into the 12 types below. They provide additional or alternative ways to collect, transfer, store, organize, manage, aggregate, structure, analyze, verify, visualize, and interpret data.

Figure 2.4: Tool Type Categorization

Most importantly, technical tools require technology to function. They usually use ICT and are enabled by a technological boom-increasing coverage by 3G or 4G internet or satellite access and increasing mobile phone ownership, for example. Even in rural communities, mobile communication sometimes becomes available even before access to electricity is provided.

However, there are frequently limitations: although 3G/4G internet might be widely available, the quality and reliability of the connection plays a key role. When PAP are concerned, certain aspects must be considered, such as whether they truly have access (proper connection, digital literacy, familiarity with the selected tools) and whether the selected method is appropriate (data protection concerns, people being comfortable with expressing their opinion through a given platform, cultural appropriateness, etc.).

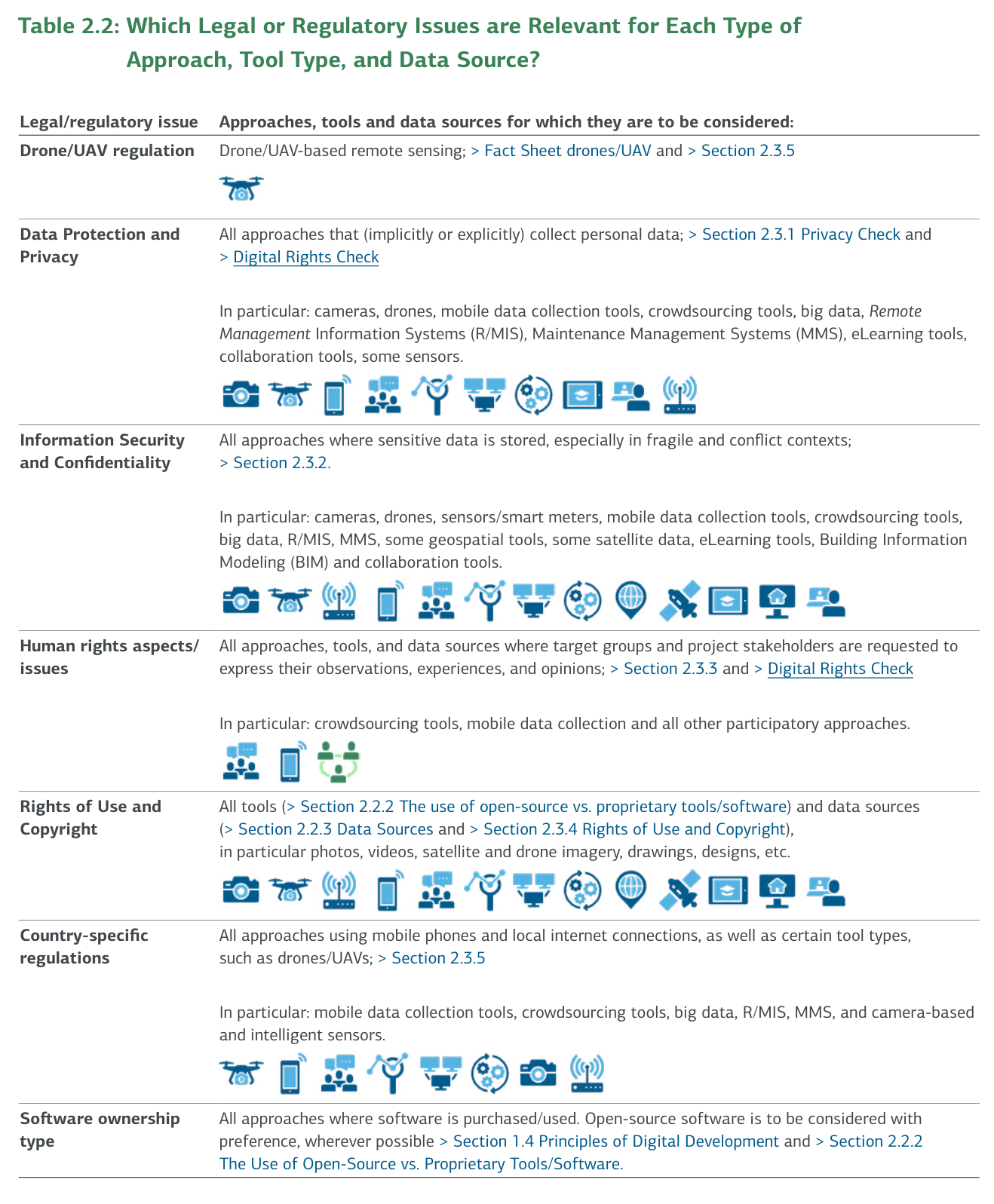

Figure 2.5: Tool Types According to Data Type

2.2.2 The Use of Open-Source vs. Proprietary Tools/Software

A fixed and essential component of the use of technical tools in RMMV is the associated software. Software licenses govern the use and redistribution of software. According to their license, software can be divided into two main types: proprietary software and open-source software. The difference lies in whether the software grants the right to use, modify, and reuse a software product obtained by a customer or user. In general, in international development, the use of open-source software is highly encouraged.

Open-source software (i.e., non-commercial software):

The term "open-source" refers to a software product people can alter and redistribute because it is released without the usual (copyright) use restrictions. This means the developers who designed the software are happy for other people to use their software for their own purposes, and adapt and develop it as they see fit, without paying any fees to the original creator.

Examples of open-source products are WordPress, Open Office, the internet browser Mozilla Firefox, Wikipedia, the GNU/Linux operating system, and its derivative Android, an operating system for mobile devices.

Proprietary software (i.e., commercial software):

The opposite of open-source software is proprietary software, where only the individual creators, or the business that created it, has the right to control or modify the source code. Examples of proprietary software include Microsoft Office and Adobe Photoshop - paying customers may use the software, but they may use it only for the purposes expressly permitted by the creators.

Open-Source Software Pros and Cons:

Advantages:

- Open-source software tends to have relatively high setup/configuration costs, but low running costs

- Generally highly reliable due to the higher number of developers included during the software development

- Versatility: Using open-source software means that software operators are not locked into using a particular vendor's system

- More secure because it is much more thoroughly reviewed and vetted by the community

Disadvantages:

- Open-source solutions do not exist for all application purposes

- Lack of support: In contrast to proprietary software, there is no institutionalized helpdesk users can turn to if things go wrong

- Liabilities and warranties: Open-source software licenses typically contain only a limited warranty

Proprietary Software Pros and Cons:

Advantages:

- Proprietary software offers customer service and is tailored to market needs

- The purchase of a proprietary software product normally includes long-term license fees, maintenance, and other services

Disadvantages:

- Long-term licensing fees and (later) adjustments to the proprietary software increase the operation and maintenance costs

- Dependency on one company (the lock-in effect)

- Proprietary software can quickly become out-of-date if the provider ceases to support it

2.2.3 The Use of Data Sources

Today, data is an important resource for operations in virtually every field and sector. Data helps us to gain a better understanding and thus make better decisions. Data-based work does not mean relying solely on data and numbers but incorporating them into decision-making. Data helps to systematically record and describe past and current situations and to measure effects.

2.2.3.1 Key Elements in the Identification of Data Sources within the Project Cycle

Project Preparation Phase: Before using any data, it is necessary to formulate adequate questions. Being very clear about the information needs, formulating key questions and information collection goals is the first step in data analysis and often is not adequately done beforehand. This creates many problems later because often data is collected that is not fit for the purpose.

During Project Implementation: During the implementation of a project, it is important to track its progress via its activities and outputs and its impact on its social and natural environment. The same applies to external factors that may jeopardize the success of the project.

End of Project: In the later stages of the project cycle, in addition to the outputs, the evaluation of the project outcomes and the impact can be significantly informed by external data sources.

2.2.3.2 Key Elements in Data Analysis

Data samples as well as all information derived from them can only ever represent a section of reality, therefore, it is important to understand the data and model limitations, and maintain critical thinking. When considering a data set, the methods used to collect the data must be questioned and presented transparently.

2.2.3.3 Systematic Bias and Potential Risks

Systematic biases, that is, unintended distortion in your data, due to an unbalanced choice of observations, pose a risk of incorrect conclusions being drawn from it, leading to erroneous decisions and project interventions. When conducting surveys, in particular, care must be taken to ensure that the type of survey or the selection of respondents does not exclude any social groups.

2.2.3.4 Equal Access to Data Sources

The aforementioned issue of the responsible use of data also includes facilitating access to data (sources) for those from whom the data was collected and who form the target group of the projects. This includes not only the project partners but also the local people, communities and the whole public.

2.2.4 Open Data

Open data includes all data that can be freely used, reused, modified, and redistributed by anyone-subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and share alike. With Open Data, in addition to the non-existent licensing costs for data use, universal participation is strengthened.

Open Licenses

By definition, Open Data (or data sources) should be provided along with an open license that ensures that the data can be used openly as described above. The most important licenses for Open Data are:

- Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY-4.0): Allows the open usage of data, attribution is required

- Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 4.0 (CC-BY-SA-4.0): Allows open use of data, requiring attribution and publishing the derivative product under the same terms

- Open Data Commons Attribution License (ODC-By-1.0): Allows the open usage of data, attribution is required

- Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL-1.0): Allows open use of data, requiring attribution and publishing the derivative product under the same terms

2.2.5 Non-Open Data from External Sources

Non-open external data refers to third-party owned data whose availability or usability is technically or legally restricted. It may be freely available, but its use may be restricted to specific purposes, or it may be exchanged or acquired for payment as part of data partnerships.

2.2.6 Existing Data from Project Stakeholders

Using your own data, if available, is the easiest way. Organizations specify rules, principles, and guidelines of data management in a data policy. Provided that a corresponding data policy has been implemented in your organization and is known to you, definitions of terms and quality standards are uniform, and technical access is usually not a problem either.

2.2.7 Big Data

The term "big data" is not precisely defined, but there is a general understanding of what type of data is being referenced. As a rule of thumb, big data describes a quantity of data that cannot be processed or stored by a normal computer. This may be due to the actual volume, the variety of data formats (esp. unstructured/non-tabular), or the speed at which new data sets are added or generated.

One possible application is the use of already collected data from private organizations for the public good in a privacy-conscientious, scalable, socially, and economically sustainable manner.

2.3 Legal and Regulatory Conditions and Recommendations

Successful application of institutional RMMV approaches, tools and data sources depends on the situation in the country or target area, including political, social, legal and regulatory conditions, as well as local ICT access conditions. Issues that should be considered include the human rights situation, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)/drone regulation, information privacy (how personal data is handled), data security (how data is preserved), local IT access conditions, and software ownership types (whether to use open-source or proprietary software).

Table 2.2: Which Legal or Regulatory Issues are Relevant for Each Type of Approach, Tool Type, and Data Source?

| Legal/regulatory issue | Approaches, tools and data sources for which they are to be considered |

|---|---|

| Drone/UAV regulation | Drone/UAV-based remote sensing |

| Data Protection and Privacy | All approaches that (implicitly or explicitly) collect personal data |

| Information Security and Confidentiality | All approaches where sensitive data is stored, especially in fragile and conflict contexts |

| Human rights aspects/issues | All approaches, tools, and data sources where target groups and project stakeholders are requested to express their observations, experiences, and opinions |

| Rights of Use and Copyright | All tools and data sources, in particular photos, videos, satellite and drone imagery, drawings, designs, etc. |

| Country-specific regulations | All approaches using mobile phones and local internet connections, as well as certain tool types, such as drones/UAVs |

| Software ownership type | All approaches where software is purchased/used. Open-source software is to be considered with preference, wherever possible |

2.3.1 Data Protection and Privacy Requirements in Financial Cooperation

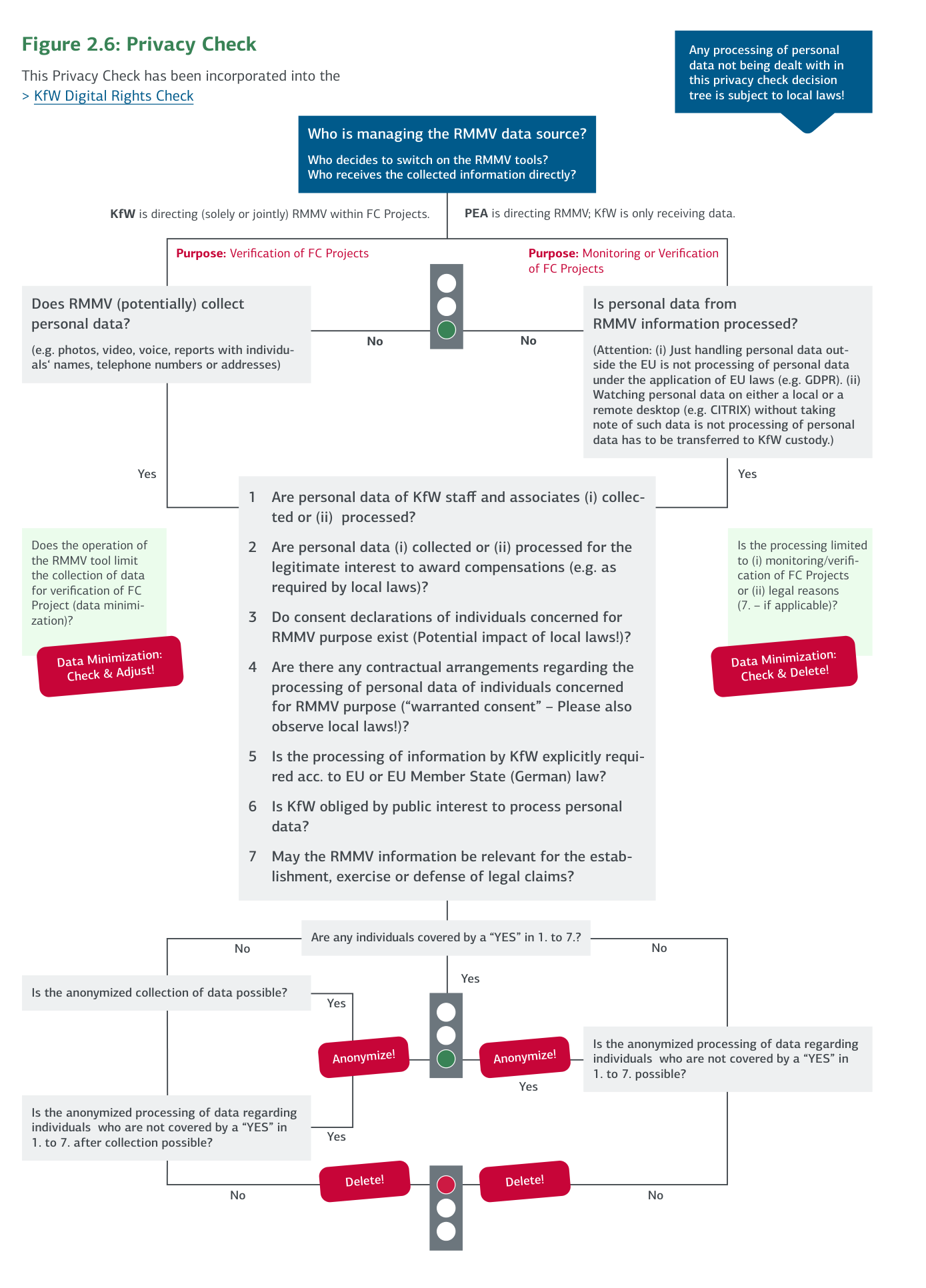

As a first rule and best-practice approach, avoid collecting any personal data if it is not absolutely required. Wherever possible, avoid using personal data and strictly limit your information needs to an aggregated data level that protects the privacy of data providers.

Data privacy, also known as information privacy, refers to the necessity to preserve and protect any personal data collected by any organization from being accessed and processed by a third party.

Box 3: Personal Data

Definition of personal data in EU law: Personal data is defined as "any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person." A low bar is set for "identifiable"-if anyone can identify a natural person using "all means reasonably likely to be used," the information is personal data, even if the organization holding the data cannot itself identify a natural person.

Data privacy needs to be considered for all RMMV approaches, tools, and data sources that potentially, or actually process (including implicitly or explicitly collecting or recording) any personal data. They are mainly mobile data collection and crowdsourcing tools, (R)/MIS, MMS, cameras or UAVs/drones, some other types of sensors, eLearning tools, collaboration tools, and big data.

The following principles should be assured:

- Notice: persons should be given notice when their data is being processed

- Purpose: data should only be used for the predefined purpose stated and not for any other purposes

- Disclosure: persons should be informed as to who is collecting their data

- Consent: data should not be disclosed without the data subject's consent

- Security: collected data should be kept secure from any potential abuses

- Access: data subjects should be allowed to have access to their data and be able to make corrections

- Accountability: persons should have a method available to them to hold data collectors accountable

Figure 2.6: Privacy Check

2.3.2 Information Security and Confidentiality in Financial Cooperation

Information security refers to protective measures that are applied to achieve the following primary goals and objectives:

- Confidentiality: Objects are not disclosed to unauthorized subjects

- Integrity: Objects retain their veracity and are intentionally modified only by authorized subjects

- Availability: Data, objects, and resources are accessible uninterrupted and efficiently

The most common problems regarding data security are the following:

- Insufficient data protection

- Employee negligence

- Employee mobility

- Failure to routinely back up data

2.3.3 Human Rights Aspects

All RMMV approaches where target groups and other project stakeholders are requested to express their experiences, observations, and opinions may be affected by limited respect for human rights, particularly limited freedom of speech and opinion and limited freedom of the press.

Limited freedom of speech or limited freedom of the press may render RMMV approaches for which target groups share observations and experiences inapplicable or may put individuals at risk. People may be hesitant to express negative experiences or dissatisfaction with projects or government programs in general since they may fear disadvantages or retaliation by the government.

2.3.4 Rights of Use and Copyright

The KfW consulting contract should stipulate that the consultant shall transfer to the Employer (i.e., usually the PEA) and KfW all rights to the services performed under this Consulting Contract on the date any such rights arise, and in any event at the latest on the date they are acquired by the consultant.

2.3.5 Country-Specific Regulations Regarding the Use of Certain Tool Types

When planning to deploy a specific tool or software or to publish a data source, always check for country-specific regulations on copyrights, rights of use, privacy, and Information Security.

In particular, certain tool types are frequently subject to national regulatory restrictions: Drones/UAVs, Mobile Data Collection, Crowdsourcing tools, GPS tracking, use of high-resolution Satellite Imagery of certain areas, the permission for certain Collaboration Tools, as well as regulations on machine learning/AI relevant to Big Data generation and use.

2.4 Supporting IT infrastructure for Remote Verification

2.4.1 RMMV Rooms at KfW HQ

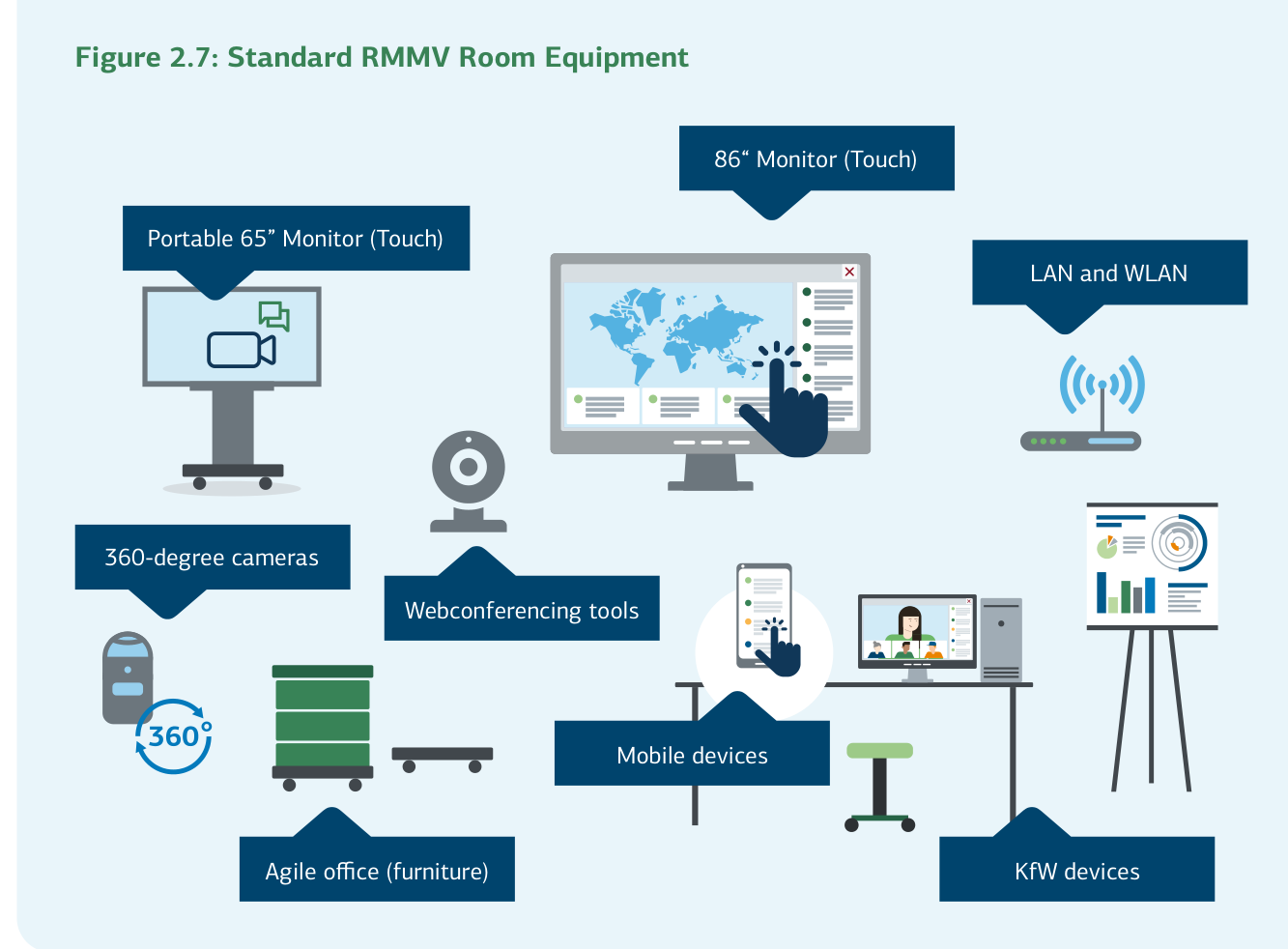

For collaborative work in the context of RMMV, KfW has installed so-called RMMV rooms at its headquarters in Frankfurt. From these special rooms, many tools like Skype, MS Teams, Zoom, Webex, etc. can be used, as well as software like Google Earth Pro and QGIS.

Examples of use cases:

- Virtual site surveys

- Evaluating satellite images

- Collaborative work via web and video conferences

- Conducting virtual workshops with the virtual whiteboard software Conceptboard

The rooms are equipped as follows:

- One fixed large touch screen (86 inches)

- One mobile touch screen (65 inches)

- A conference solution with a 360-degree camera

- Access to the KfW network and access to the public internet via WLAN

- Conference telephone

- Android and iOS Tablet

- KfW laptop with docking station

- Many adapters to connect the different devices

Figure 2.7: Standard RMMV Room Equipment

2.4.2 IT Infrastructure at the Country Office Level

KfW's core business includes maintaining a large and ever-changing number of international country offices. KfW's IT department is currently managing approximately 2,300 operationally relevant IT infrastructure components at 75 FC and IPEX locations.

Most KfW country offices have a large local data storage facility called NAS (Network Attached Storage). Migration to cloud storage solution is planned for 2025.

The following equipment essential for Remote Verification is currently being generally rolled out in KfW's country offices: Centrally serviced standard smart phones for all national project staff thus providing them access to the relevant KfW apps and collaboration tools, video conferencing and video documentation hardware and software including meeting owls, as well as hardware and software for conducting virtual site visits including 360° cameras and virtual reality (VR) goggles and satellite communication devices.

2.5 The RMMV Decision Matrix for Selecting the Appropriate Mix of RMMV Institutional Approaches, Tool Types, and Data Sources

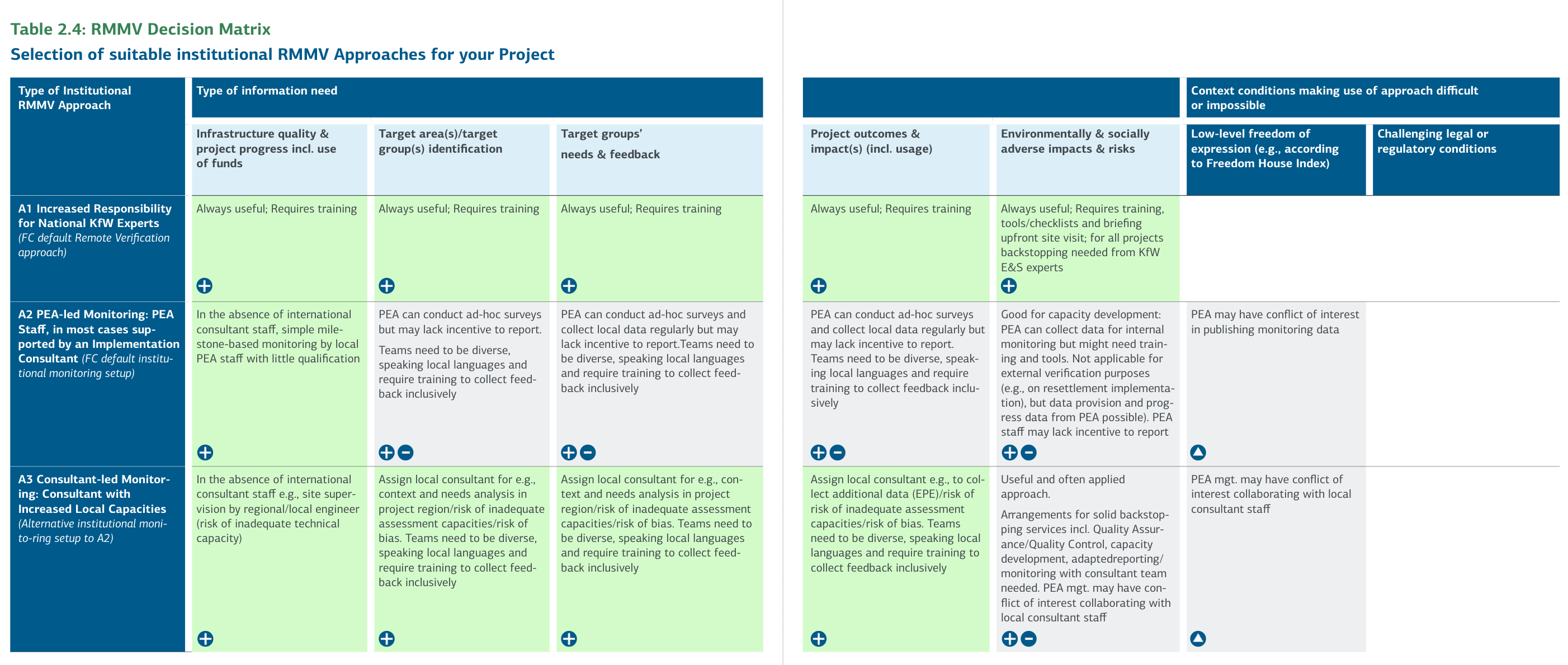

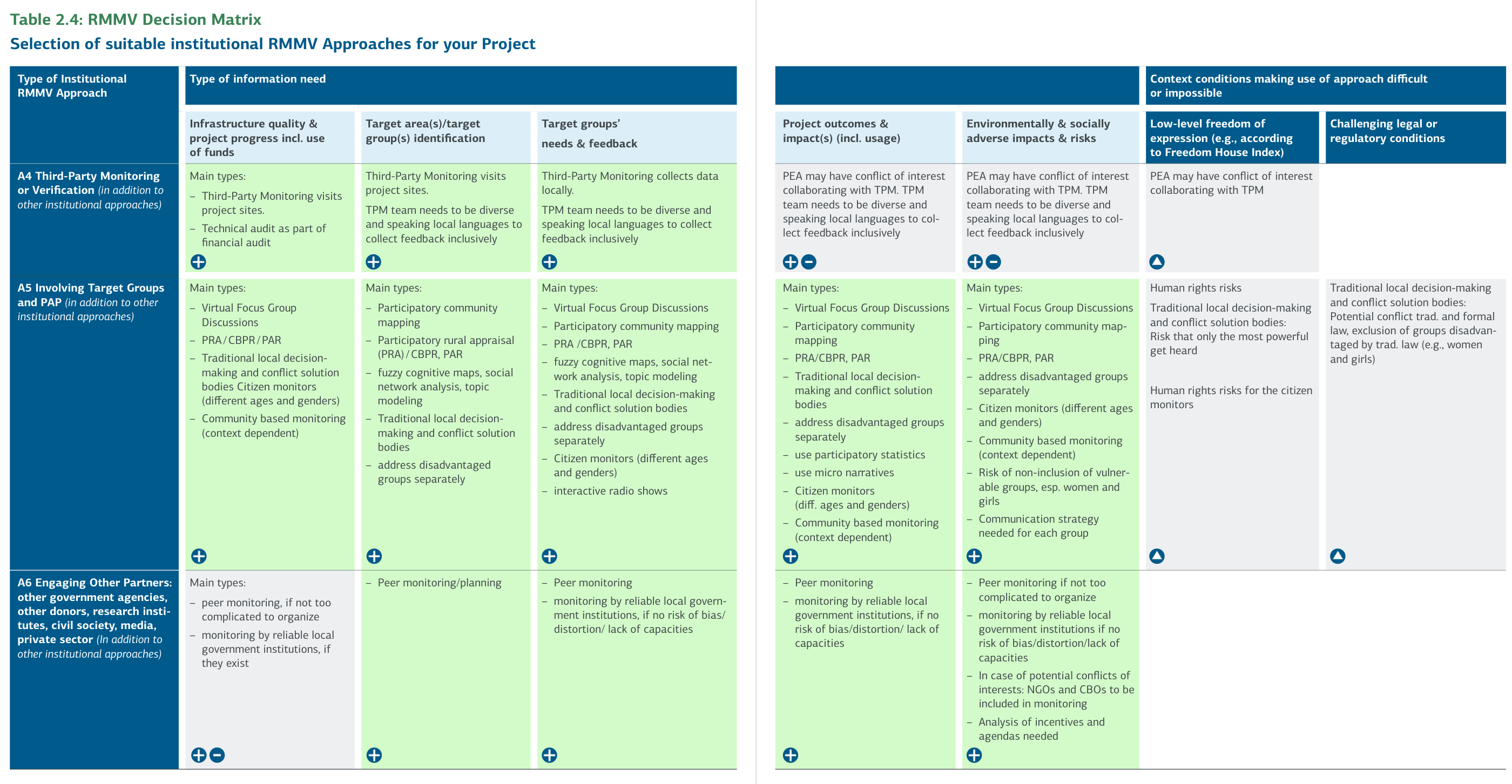

Because of the multitude of different institutional approaches, tool types and data sources, a Decision Matrix has been developed to help KfW as well as PEA and consultant staff to jointly determine which mix of institutional RMMV approaches, technical tool types and data sources is particularly useful for the specific project.

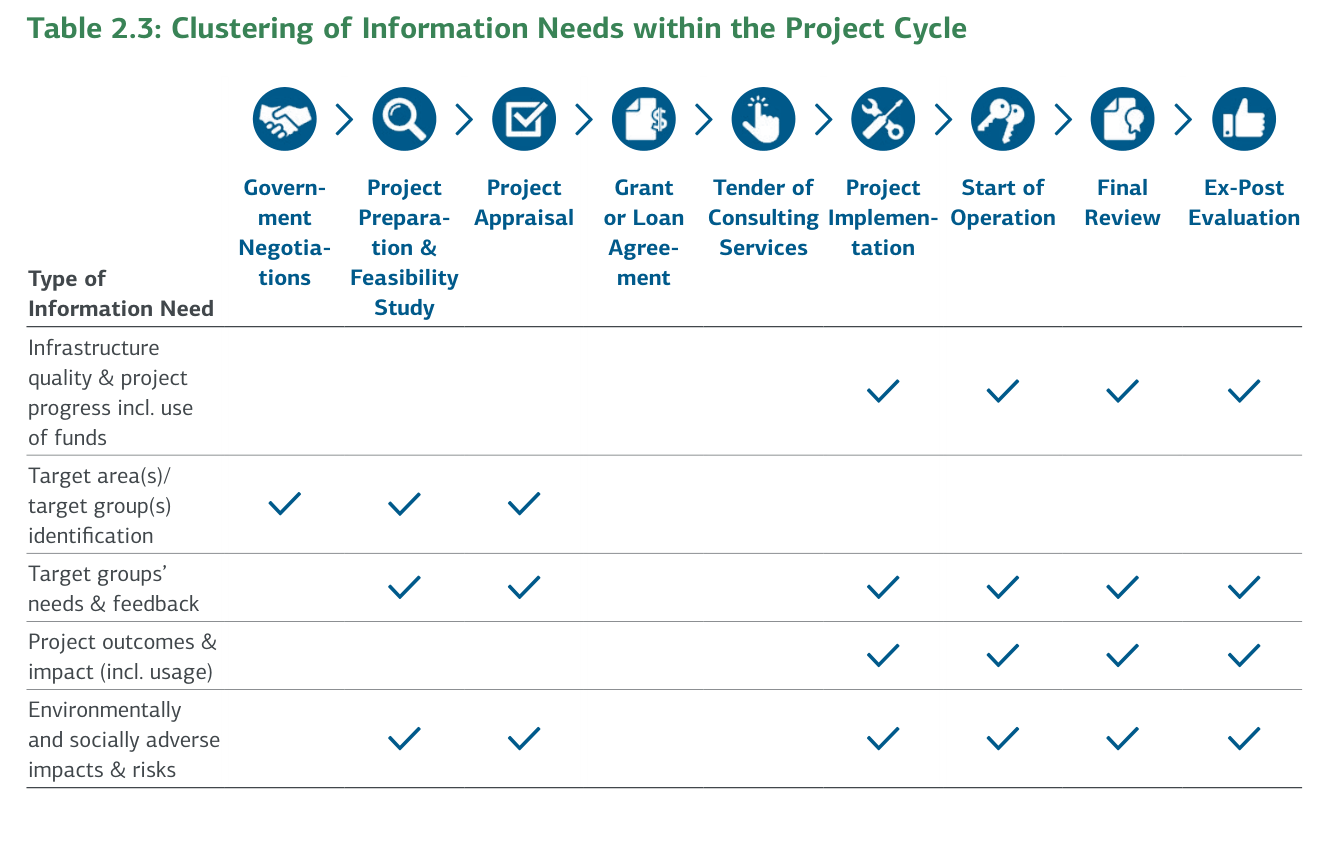

To provide orientation on the usefulness of different institutional approaches, technical tool types, and data sources, information needs have been clustered into five general types that occur throughout the project cycle:

- Infrastructure quality and project progress including the use of funds

- Target area(s)/target groups' identification

- Target groups' needs and feedback

- Project outcomes and impact (including usage)

- Environmentally and socially adverse impacts and risks

Table 2.3: Clustering of Information Needs within the Project Cycle

| Government Negotiations | Project Preparation | Project Appraisal | Grant or Loan Agreement | Tender of Consulting Services | Project Implementation | Start of Operation | Final Review | Ex-Post Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2) Target area(s)/target groups identification | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds 2) Target area(s)/target groups identification 3) Target groups' needs and feedback 5) Environmental and social adverse impacts and risks | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds 2) Target area(s)/target groups identification 3) Target groups' needs and feedback 5) Environmental and social adverse impacts and risks | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds 5) Environmental and social adverse impacts and risks | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds 3) Target groups' needs and feedback 5) Environmental and social adverse impacts and risks | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds 3) Target groups' needs and feedback 4) Project outcomes and impact (incl. usage) 5) Environmental and social adverse impacts and risks | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds 3) Target groups' needs and feedback 4) Project outcomes and impact (incl. usage) 5) Environmental and social adverse impacts and risks | 1) Infrastructure quality & project progress incl. use of funds 3) Target groups' needs and feedback 4) Project outcomes and impact (incl. usage) 5) Environmental and social adverse impacts and risks |

Applicability of certain institutional approaches or technical tool types and data sources per information need category

The matrix shows how each institutional approach and tool type (incl. data source) supports information gathering for a respective information need category:

Legend:

- 🟢 The approach/tool type is particularly useful

- 🟡 The approach/tool type may be applied, but risks need to be taken into consideration

- 🔴 The approach/tool type is potentially harmful (human rights risks) if risks cannot be mitigated

- ⚪ The approach/tool type is not relevant or useful

Context conditions that might limit the use of an approach or tool type:

- A fragile or conflict context implying a low level of governance, represented by "a low level of freedom of expression in a target country"

- Legal and/or regulatory restrictions on the respective RMMV approach or tool type within a given country or area

Table 2.4: RMMV Decision Matrix - Selection of suitable institutional RMMV Approaches for your Project

*Note: The information drawn from the Decision Matrix is by no means complete and has been shortened/summarized to not jeopardize the readability of the matrix. Conclusions drawn from it need to be checked for plausibility and reflected within the specific design of the RMMV institutional approach, tool, or data source, and its respective project context. KfW can therefore not be held liable for any use or any conclusions drawn from this Decision Matrix, and specific advice should always