3. RMMV within the Financial Cooperation Project Cycle

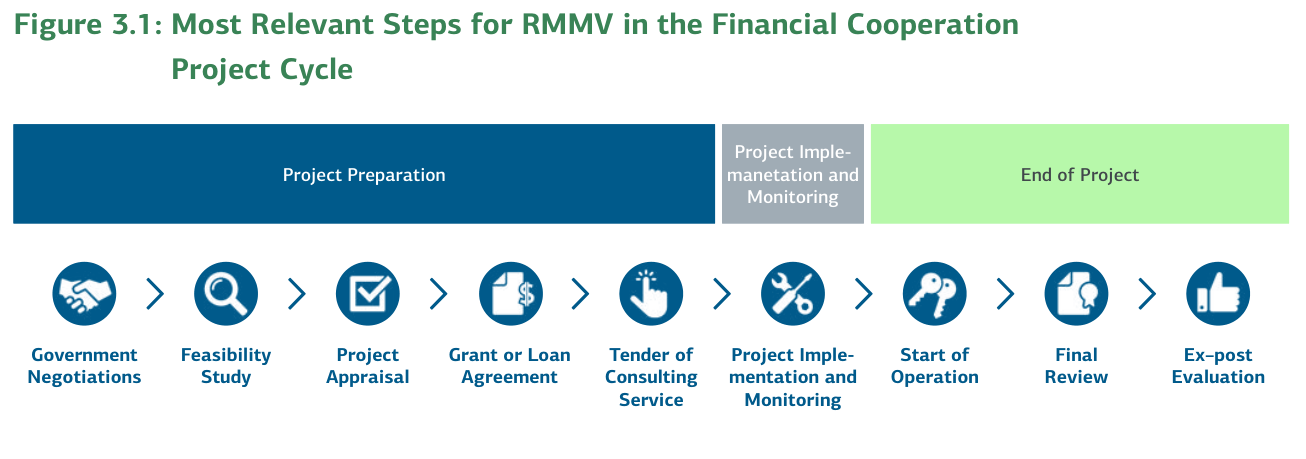

This Section offers concrete practical advice to all Financial Cooperation (FC) project stakeholders for managing a FC project remotely. It describes the relevance of RMMV for each step along the FC project cycle and provides tangible recommendations on what needs to be considered during each step, as well as checklists, templates, and examples. KfW must adapt its own approaches and tool types to be able to conduct its crucial verification tasks (project appraisal; progress reviews, including verification of the use of funds; final reviews; and ex-post evaluation) despite limited access to project sites and target groups. It is important to note, however, that the recommendations of this Guidebook do not replace or change any official KfW procedures during the FC project cycle, but rather provide assistance to KfW and its implementing partners in how to execute these procedures in a remote modality.

Although this Guidebook refers to KfW's mode of operation, the principles can, of course, be transferred to the business models of other development stakeholders.

Figure 3.1: Most Relevant Steps for RMMV in the Financial Cooperation Project Cycle

3.1 Project Preparation

For KfW to fulfill its obligations stemming from the general contract with BMZ and the > General Guidelines for the German Technical and Financial Development Cooperation (only available in German) along the FC project cycle, the mix of RMMV approaches, technical tool types and data sources must be developed as early as possible in the project cycle, agreed with the implementing partners, and designed to suit the project stakeholders' needs. This Section outlines the key steps in project preparation and outlines central considerations around the integration of RMMV at this stage: This covers both the use of RMMV during project preparation in a situation with limited access to project sites and the design of the RMMV approach for project implementation that needs to be developed and agreed on during the project preparation phase.

3.1.1 Government Negotiations

The FC implemented by KfW is based on the country strategy of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the development strategies of the partner country. The projects and programs supported are proposed at bilateral government negotiations, and the German government decides up to what level funding is to be committed. An intergovernmental agreement is concluded on the sector and type of projects that are going to be supported. This first step in the project cycle is important for RMMV for the following reasons:

-

Government negotiations present an opportunity to define the (sub-)sectoral focus of the future financial engagement, > Section 3.1.1.1 below

-

They require preparatory work by KfW and the potential project partners in pre-assessing the feasibility of proposed project ideas within the defined (sub-)sector, so that non-feasible ideas can be dropped in time,

Section 3.1.1.2 further below.

- They present an opportunity to anchor the prerequisites for the mix of RMMV approaches for the proposed project idea early on, including particularly:

agreeing on granting KfW access to the relevant project data sources (e.g., to the project-related part of the PEA's management information system), > Section 2.2.3 Data Sources and > Fact Sheet (Remote) Management Information Systems protecting the interests of target groups and other stakeholders involved in RMMV where their data privacy and security or any other human rights aspects might be affected (e.g., by agreeing on a citizen feedback crowdsourcing mechanism as part of the project design), > Sections 2.3.1 on Data Protection & Privacy, > 2.3.2 on Information Security & Confidentiality and > 2.3.3 Human Rights Aspects enabling the use of intended RMMV technical tool types (e.g., UAVs/drones) via exemptions from respective laws or regulations, as necessary, > Sections 2.3.4 Rights of Use and Copyright and > 2.3.5. Country-specific Regulations.

3.1.1.1 Choice of Sector, Region, and Financing Instrument

Before and in parallel with government negotiations, KfW is requested by its German government clients to gain an overview of the (sub-)sector under discussion and to identify potential interventions based on the proposals submitted by the partner government. At this stage, KfW starts reviewing whether the proposed projects are developmentally sound and realizable. The choice of (sub-)sector depends on both countries' development strategies and policies, the core areas of intervention agreed upon between the German government and the respective partner country government, the needs and capacities of the prospective target groups, the capacity of the potential PEA and the evaluation of potential issues and risks.

With regards to RMMV, there are some sectors and financing instruments that are less affected by challenges and risks resulting from reduced site access because these largely rely on partners' systems and do not require any physical checks on project progress and use of funds, such as program-based approaches like policy-based lending or basket funds in the governance sector or financial sector support projects or (co-)financing of UN programs (they do however require other pre-conditions to be met). Most bilateral infrastructure or environment projects do require physical checks of at least a sample of (prospective) sites. The more complex a project is, the more challenging its remote implementation becomes. This needs to be considered when agreeing on the (sub-)sector and financing instrument > Section 3.1.1.2 below. Flexibility in choosing target regions for the intervention is especially important in fragile and conflict-affected environments, so that in case a proposed target region becomes inaccessible, another region can be selected instead. If the target region has been defined during government negotiations without alternatives or flexibility, adaptation strategies become difficult.

3.1.1.2 Pre-assessing the Feasibility of Proposed Project Ideas

Before the government negotiations take place, the project partners need to make sure that the sectoral and regional focus of an FC engagement and possible project ideas can realistically be implemented, if necessary through a mix of institutional RMMV approaches, technical tool types and data sources. While institutional RMMV approaches, technical tool types and data sources can go a long way in enabling KfW to finance projects in areas inaccessible to international staff, KfW may have to recommend its clients and partners to drop a project idea entirely from the list of projects before or during government negotiation in the following cases:

- Complex project ideas that require constant international staff presence or that have obvious high environmental and social risks, such as dam construction

- Projects for which sufficient environmental and social data to inform decision-making cannot be collected in a timely and/or reliable manner

- Project areas that are completely inaccessible most of the time to local project staff

- Project regions or areas where electronic data collection devices cannot be used

- Projects that require the direct involvement of target groups in RMMV that are being implemented in countries that have a significant lack of freedom of expression, because the social risk would be too high that an individual becomes negatively affected by his/her participation or feedback, which could, in addition, create unacceptably high reputational risks for KfW, > Sections 2.3.3 Human Rights Aspects, > 2.5 RMMV Decision Matrix and > 3.1.1.3 Environmental and Social Risks Categorization.

If one of the chosen RMMV approaches requires significant investment or requires the partner government to collect, share, publish or improve data or its own data systems (see also Case A mentioned in the > Fact Sheet (Remote) Management Information Systems), it is advisable to refer to the respective RMMV clauses to be agreed during project appraisal (> Section 3.1.3 Conducting Project Appraisals Remotely) and for this to be stated in the project's Grant or Loan or Separate Agreement (> Section 3.1.4 Contractual Considerations) and/ or in the respective consultant contract (> Section 3.1.5 RMMV Aspects in the ToR, Tendering and Contracting of Consulting Services) upfront in government negotiations, as this may affect the overall feasibility of the project idea. Partner governments may be hesitant to share their own data, publish critical information, or update their systems for various reasons. They may be concerned about criticism appearing online or may not prefer information of religious or ethnic composition to become publicly available. However, government willingness is crucial for some RMMV approaches, such as crowdsourcing tools that require an online platform where people can provide feedback or government-owned (Remote) Management Information Systems or Maintenance Management Systems where KfW requires access to partner country systems. If this is the case, a mix of institutional RMMV approaches, technical tool types and data sources should be discussed during government negotiations and recorded in the minutes of meeting to secure government buy-in early on. Mentioning planned institutional RMMV approaches, tool types and data sources during government negotiations demonstrates the transparency of the FC partners' objectives and outlines the government's responsibility for their appropriate uses. This creates mutual trust and allows BMZ and other KfW clients to officially address any upcoming RMMV issues in the future. This was for instance successfully done in the > Decentralization Support Program in Togo (PN: 30205), where a mobile crowdsourcing-based citizen feedback-loop system was introduced and already mentioned during government negotiations.

What to write in the Summary Records of the Government Negotiations If relevant, briefly mention the proposed mix of institutional RMMV approaches, tool types and data sources in the summary records and refer to the RMMV Guidebook published on KfW's website for further information. For example, "Creation of a monitoring system by citizens in selected towns for the citizens to be able to participate in infrastructure planning and to monitor construction progress in their town."

3.1.1.3 RMMV Approaches for E&S Risk Categorization at the Stage of Project Idea

In preparation for the government negotiations, every new project must be categorized by KfW into an environmental and social risk category (A, B, B+, C) at the stage of the project idea before submitting the project concept note to the BMZ or another KfW client. Therefore, the KfW-HQ-based PM, decentralized Environmental & Social (E&S) expert and the respective technical expert fill out the project categorization table and assign a category which is verified by the Competence Centre for Environmental and Social Sustainability (KCUS). For the E&S category verification, the KCUS is regularly applying RMMV approaches for all projects, including those that could be developed and managed with physical presence. The reason for using RMMV approaches is that this verification is an initial screening of potential E&S risks and impacts where KfW wants to get a quick indication of potential risks.

For this task, satellite images are used to see the potential project site(s), screen as to whether natural or critical habitats may be affected and identify deforestation. Databases and data analysis tools like > IBAT (Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool) or > protectedplanet.net are frequently used to identify protected areas and migration pathways, for example. Similarly, satellite pictures can reveal whether physical resettlement or economic displacement will be necessary by identifying houses, agricultural fields, grazing grounds, and other relevant structures. This enables gauging losses early on in the project in order to estimate the costs and resources needed for the resettlement and livelihood restoration process.

Currently, > Google Earth Pro images are used as well as > OpenStreetMap, > Bing maps, and similar. Google Earth has a useful functionality: in the history you can see images taken in the past, which often yields a good indication of movements of people into the project region over time and changes in land use over time and by season. However, Google Earth images are not updated very frequently for several regions of the world, which means that current images may not be available, especially in remote areas. Urban areas are updated more frequently. In addition, the resolution of Google Earth images varies for several regions, with rural areas often having lower resolution. Due to the limitations of Google Earth, the use of publicly available data (e.g, from the Copernicus program) and/or commercial data (e.g., Planet Labs, Maxar, or Nearmap), where custom tasked imagery or regular revisit imagery can be purchased, is also recommended. Some companies provide data on a daily or sub-daily basis, which makes it very suitable for E&S assessment, > Fact Sheet Earth Observation via Satellites and > Fact Sheet Data Sources.

The application of satellite data can be also used for the early estimation of losses and those data can be also used for avoiding opportunistic behavior, such as people moving into the project area before the cut-off date.

Besides geographic information, there are several other information sources (> Section 2.2.3 The Use of Data Sources) for screening environmental and social risks, such as for screening indigenous peoples (IP) in Latin America. For such screenings, you can use > http://peoplesoftheworld.org/bycountry or LandMark(> https://landmarkmap.org) and > https://www.iwgia.org/en/. The two latter sites also offer maps and reports.

Google searches can also assist with getting contextual information, for example, on the application of International Labour Organization (ILO) core labor standards or searching for similar projects in the region as well as on pre-assessing human rights risks, > Section 2.3.3 Human Rights Aspects. KfW is currently developing an Open Data Platform to facilitate easy access to the main relevant open-data sources in the context of international development cooperation. This platform will include data sources needed for assessing environmental and social risks and impacts.

3.1.2 Feasibility Study

Following the government negotiations, KfW examines whether the proposed projects are adequate to address the development needs of the respective country and are feasible. Specialized consulting firms work with partner governments to prepare a Feasibility Study to address all the important questions about the project-economic viability, developmental impact and possible risks. Social, cultural, and ecological aspects are taken into account.

RMMV needs to be considered in the Feasibility Study in two ways:

-

Consultants conducting a Feasibility Study can be encouraged or obliged to use institutional approaches, technical tool types and data sources themselves for their assessments, especially if they cannot access the (entire) project region or all prospective project locations, and/or if they have to work remotely themselves. Consultants should be obliged to systematically use existing (open) data sources in all cases.

-

During the Feasibility Study, the project design and thus the mix of institutional RMMV approaches, tool types and data sources to be applied is typically developed.

3.1.2.1 Application of RMMV Approaches in Conducting the Feasibility Study

International feasibility consultants are to use RMMV approaches themselves, especially, but not exclusively when they are unable to visit the project region and target group(s). Feasibility consultants need to analyze the context and needs and the target group(s), consult with stakeholders, and collect baseline data. The consultant is to propose the best institutional RMMV approaches, tool types and data sources to carry out the Feasibility Study. A few examples are outlined below:

- Use relevant RMMV (open) data sources including satellite data (> Fact Sheet Earth Observation via Satellites) as part of the desk study/mission preparation. This is especially useful to determine the baseline indicators, control groups and relevant context factors and risks.

- Assign national/local consultants (ideally male and female speaking local languages) for context and needs analysis in project region: the feasibility consultant subcontracts local experts to assess needs, speak to stakeholders and target groups and visit potential project sites > Institutional RMMV Approach A2.

- Assign local consultants to collect target groups' opinions through participatory methods: local consultants can use participatory methods (e.g., village mapping or other methods of rural participatory appraisals) to gather feedback from target groups in order to improve project design, identify risks and devise mitigation measures, including identifying do-no-harm and environmental and social risks(> Box 2 above for a description of participative methods).

- Survey target group using mobile survey application: classical surveys of target groups can be supported through smart phone apps > Fact Sheet Mobile Data Collection.

- Evaluate population movement through use of mobile phone big data: This can be helpful to identify target areas, analyze needs and establish baselines, particularly for emergency, migration, biodiversity and transport projects (to be repeated during project launch) > Fact Sheet Data Sources.

According to KfW's evaluation department, publicly available open-data sources and satellite data in particular are chronically underused for Feasibility Studies. It is therefore recommended to use some technical tool types and data sources in general within the Feasibility Study, even if there is no access problem as part of the desk study:

- Analyze socioeconomic and other open-data platforms: needs assessment is conducted based on quantitative indicators contained on socioeconomic and other open-data platforms, > Section 2.2.3 The Use of Data Sources

- Use satellite imagery to identify target areas/sites/locations and target groups and triangulate information from other data sources, > Fact Sheet Earth Observation via Satellites.

For recommendations on how to develop the adequate mix of institutional RMMV approaches, tool types and data sources for the RMMV of the project, > Section 2.5 RMMV Decision Matrix. As not all PEA and feasibility consultants may be aware of the diversity of potential institutional RMMV approaches, tool types, and data sources or of KfW's strategy and experience in applying RMMV to its projects, this RMMV Guidebook has been published on the > KfW Website and to > Digital Rights Check allow them to learn from current practices and lessons.

3.1.2.2 Drafting ToR for the Feasibility Study to Analyze and Conceptualize the Use of RMMV in a Project

The ToR for a Feasibility Study include the entire content necessary to assess the project feasibility as well as its major design elements. Herein, only potential RMMV-specific elements of such ToR are described. These RMMV elements will then have to be adapted to the actual environment and project objectives.

a) Context and project conditions

- Sector analysis and needs assessment: the consultant can be encouraged or obliged to use relevant RMMV (open) data sources, including satellite data (> Fact Sheet Data Sources) as part of the desk study/ mission preparation.

- Analysis of human rights situation: if RMMV approaches require target groups or other local stakeholders to be directly involved in the RMMV approach, the level of freedom of expression must be analyzed and discussed, > Section 2.3.3 Human Rights Aspects and > Digital Rights Check.

- Analysis of access to ICT in the target region(s) by different parts of the target group(s) to determine the feasibility of certain technical tool types and the need for mitigating potential digital divides, > Section 3.1.2.6 Local ICT Access Conditions.

- Analysis of legal and regulatory framework regarding RMMV: the consultant is to analyze the legal and regulatory framework regarding prospective institutional approaches, technical tool types and data sources (> Section 2.5 RMMV Decision Matrix) to assess whether these are legal and feasible in a given context, or if it is necessary/recommendable to negotiate exceptions. This assessment must also include as a focus the country-specific data protection, privacy, information security, rights of use and hardware and software import regulations relevant to the prospective approaches, tool types and data sources, > Section 2.3 Legal and Regulatory Conditions and Recommendations.

- Analysis of the PEA's capacity, management and monitoring structure and processes to jointly determine the institutional project setup, including the related suitable institutional RMMV approaches and the role(s) of the PEA within the project's RMMV approach. The assessment of PEA capacity gaps also informs the ToR of the consultant(s) required to assist with the project implementation and monitoring, > Section 3.1.2.4 Stakeholder Analysis and Incentive Model.

- Analysis of the security situation and access to the project region for all stakeholders (KfW international and national experts, PEA staff, suppliers, NGO and (local) government staff, international and local Implementation Consultant staff): the consultant is to assess the security threats and the degree of access to the project region and the freedom of movement for all stakeholders in order to evaluate suitability for taking over monitoring tasks.

- Development of security strategies for all stakeholders. The analysis is to differentiate between international, national, and local staff and consider multiple sources of security threats and their likelihood and severity for each group of staff, taking the current international security situation of the country as starting point, > Section 1.5.2. Risks.

- The consultant is to evaluate the PEA's existing security and risk management approaches to assess whether these are suitable and recommend adaptations as necessary. In particular, the consultant is to assess potential unintended negative consequences of protection measures on the security of local staff (e.g., obviously protected compound may render local staff visible after office hours, and thus vulnerable for attack).

b) Project concept: Propose an RMMV Approach (mix of institutional approaches, technical tool types and data sources):

- Design of a monitorable project: The consultant is to design the project in such manner as to allow cost-effective project monitoring. This is true for all FC projects, but even more so in remote contexts. Depending on the situation, this can mean for instance that the geographic spread of the measures must be limited to keep monitoring cost acceptable, or that individual project measures have to be similar in terms of design, scale, and implementation mode. If a project finances infrastructure measures of very different funding volumes, this would require different monitoring concepts, which become all the more difficult to organize if monitoring can only be done remotely.

- Development of the mix of institutional RMMV approaches, tool types and data sources as part of the project concept: The consultant is to propose an appropriate mix for project appraisal, implementation, monitoring project progress and use of funds, outcome and impact monitoring, and verification of progress and completion as well as ex-post evaluation by KfW. Furthermore, the consultant is to outline how the RMMV approach will be prepared and implemented. This includes defining responsibilities, contractual relations, tool types and data sources to be used and outlining the implications in terms of cost and duration. If software is to be used, the consultant must consider whether open-source software will be required within the ToR for the project implementation or not. Especially for projects with high or substantial E&S risks, the consultant is to propose how RMMV approaches, tool types and data sources will be used for managing those risks adequately.

- If the RMMV approach includes a (Remote) Management Information System, a Maintenance Management System, a Geographic Information System or similar complex software, the Feasibility Study must already outlined recommendations regarding their ownership type: > A general statement that open-source software is always better than proprietary is not true. However, open-source software has greater potential for long-term sustainable use because there are no license fees involved. > The selection of the appropriate software type is determined based on the objectives and the circumstances of the project. Who will be the user(s) of the software? Should the software be used by the local authorities after the project ends? Do additional capacity-building measures have to be taken to ensure its continued use? What would be the most cost-effective option? Can the software be reused or replicated for other projects with little adaptation? Is the required local expertise on hand for operating and maintaining the proprietary or open-source solution? Considering these exemplary and other questions, the choice becomes clear; see also, > Section 2.2.2 The Use of Open-Source vs Proprietary Software. > The Feasibility Study should make a recommendation regarding whether use of open-source software is to be a requirement. If this is the case, KfW PMs need to ensure that this is included in the Separate Agreement with the PEA, in the Terms of Reference for the Implementation Consultant and/or the software developer, > Cases A, B, C in the Fact Sheet (Remote) Management Information Systems.

- The concept must include recommendations for data-sharing agreements between the PEA, KfW and potentially other project stakeholders, on privacy and rights of use aspects and regarding a strategy for the security of collected data and information, > Section 2.3 Legal and Regulatory Conditions and Recommendations.

- Requests for Proposals should emphasize that consultants are to propose a RMMV concept that is context-specific as part of their technical offer.

c) Analysis of RMMV-specific risks to project success in fragile environments:

- Analysis of potential implementation risks due to the security context. The consultant is to assess the risk that lack of access and the difficult security situation may endanger the implementation of the project. If adequate monitoring cannot be ensured, it may be necessary to stop project preparation and evaluate whether the project is unfeasible.

- Analysis of access risks and contingency plans to mitigate them. In fragile contexts, access to project sites is usually fluid and projects need to be able to adapt. This may require contingency plans for the project concept (e.g., shift to a different region) and for the monitoring (e.g., assigning another stakeholder for monitoring if one stakeholder loses access).

- Analysis of environmental and social and specifically do-no-harm risks: environmental, social and do-no-harm risks of the proposed RMMV approach, including increased risks of biased reporting due to inadequate use of technical tools or unqualified local project staff, which need to be assessed and minimized through recommended mitigation measures.

The following sub-sections highlight certain key aspects relating to RMMV which the Feasibility Study is expected to cover:

3.1.2.3 The Collection of Project Location Information Based on a New Geodata Standard for Financial Cooperation Projects

This standardized Data Model for FC project location information collection has been developed by KfW to facilitate project location data collection, storage, management, and visualization of location information from Financial Cooperation projects (FC) for KfW and its partners and clients, and is to be used by consultants when conducting the Feasibility Study and by the Implementation Consultant during project implementation, > Section 3.2 Project Implementation and Monitoring.

What is Project Location Information? Project location information is data point information on the geographical end point of an international development assistance financial flow that is part of the respective project. In case exact geographical end points cannot be defined, approximate end points can be chosen which can relate to an administrative unit, or if that too is unfeasible, to the location of the project's executing agency, in order to ensure that all FC projects can be visualized on a map. Some examples:

- The location of a public infrastructure investment such as a school, hospital, road, etc.

- A location where a long-term project activity takes place, such as wildlife protection at a national park.

- A location where short-time services are offered, such as the distribution of training vouchers in a certain neighborhood of a city.

This geo standard for the FC is mainly based on the standard of the International Aid Transparency Initiative (so-called IATI standard, > https://iatistandard.org) utilized by BMZ, OECD DAC, the World Bank, the UN and other relevant international organizations. The IATI standard is used to make the data produced by the major development actors comparable, transferable, and aggregable. As further explained below, the uniform presentation of disaggregated spatial project data is to be given at the same time for internal project and portfolio management and for aggregated external publication or requests from the German government (> e.g., via the KfW Transparency Portal).

What Are the Benefits of Collecting Project Location Information? Project location data yields a unique contextual presentation of FC activities that allow for visualizing and analyzing project activities in a geographic dimension. This allows project stakeholders to answer a range of questions, such as: "What is the contextual situation of the project location?", "To what extent, how well or how poorly connected are daily activities of the population to related infrastructure (e.g., local commerce to the road network)?", "Which environmental risks could affect potential infrastructure sites, and what are the implications for site selection?", "To what extent does the project activity (e.g., support for a protected area) achieve certain outcomes or impact objectives (e.g., reduction of deforestation)?" These are just some examples of how geospatial analysis can answer specific questions or highlight risks or impacts that may not been asked before. Project location data are crucial to making other geodata sources, such as open satellite images, useful, > Section 2.2.3.1 Key Elements in the Identification of Data and Fact sheets, > Fact Sheet Data Sources, > Fact Sheet Earth Observation via Satellites and, > Fact Sheet Geospatial Tools. Furthermore, combined location data from multiple projects allow unique aggregated views on sector approaches, cumulative risks, combined impacts achieved, etc.

Benefits for KfW Portfolio Managers and Technical Experts: Overview of the geolocations of all project sites, improved analysis and comparability of geographically assignable project data with internal and external data sources, structured transfer of project location data to other external systems, improved data quality and time savings regarding the above tasks.

The KfW GeoApp, which is part of the organization's internal Portfolio Management Tool (PMT) application, receives the collected data which is to be used under the standardized FC Project Location Data Model. This enables KfW PMs to record project-related location data systematically and uniformly to make it available for regular reporting, progress reviews and verifying use of funds.

Above all, this avoids double entry of project data and enables partially automated data validation, further reducing the effort involved for data entry and data cleaning. The data collection templates (> Annex 3) become part of the ToR for FC projects (> Section 3.1.2 Feasibility Study and, > Section 3.1.5 Drafting ToR for the implementation of different RMMV approaches), so that these data are not recorded by KfW, but by the FC consultant or PEA in such a way that it can be uploaded to the KfW system without additional effort.

Geospatial information about the (prospective) project implementation sites is furthermore of great relevance to facilitate project site identification, field visit preparation, monitoring and verification (e.g., during project appraisals or progress reviews), for portfolio and risk analysis and for evaluation of FC-supported projects (see above) as well as many further information needs across the entire FC portfolio.

Some KfW clients are already requesting geographically differentiated project portfolio information, which is currently very time-consuming to provide. Using the GeoApp will significantly reduce this effort. The representation of the project location information on a map makes it easier to understand the situation, allowing for direct comparison of planned or actual project activities against local contexts using additional map layers from external, mostly open-data sources, > Section 2.2.3 The Use of Data Sources.

Benefits for KfW Management, Competence Centers and Country Teams: Comprehensive overview of all project locations, location-related risk and SWOT11-assessments

Once collected in the standardized format, location-related project data can be filtered, aggregated and disaggregated across countries, sectors and portfolios and analyzed and compared against each other without any additional manual effort. The automated retrieval of project location data (replacing the previous manual collection via Excel lists) reduces the effort involved in processing requests from clients and government decision makers for the competence centers and country teams. The uniform definition of location types with their geo-coordinates contained in the FC Project Location Data Model enables the use of risk analysis tools from international insurance providers, which reduce the effort involved in estimating credit default risks, risks for achieving development goals and expected damages. At the same time, gap analysis is facilitated and business opportunities can be identified more easily.

Benefits for clients, partner countries, other development banks, the public: Greater external transparency, easier identification of opportunities for cooperation with external actors, improvement in the international IATI ranking

The platform-independent structuring of key project location information based on the IATI standard enables automatic import and export of these data to other internal and external applications, e.g., for the, > KfW Transparency Portal at www.kfw.de, as well as for clients and partner systems. This facilitates the identification of synergies, gaps and collaboration opportunities for all relevant actors and stakeholders in the target area(s).

How Is the Project Location Information Collected and Stored within KfW? The collection of location information is to be organized within KfW in accordance with the FC Project Location Data Model, which is based on the IATI standard, and with a number of best practices of other development organizations and already existing standards for geospatial data. The FC Project Location Data Model specifies which location data and how location data are to be collected by the projects. The location data are to be provided by PEA staff, Implementation Consultants and/or other stakeholders who work for the respective project. Data collection should be conducted following the FC Project Location Data Model and specific technical requirements detailed below > Annex 3 KfW's Project Location Data Collection and Management Approach.

11 SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats

KfW furthermore offers a standard Sample Terms of Reference (ToR) for project location data collection (> Annex 3.2), which also includes the technical specifications from > Annex 3.1.

These ToR should ideally be part of the Feasibility Study if the potential project locations can already be identified at this stage. The ToR should then be part of the Reporting Annex of the Project's Separate Agreement and/or the ToR and Contract of the consultant to be tasked with project monitoring and reporting and/or project location data collection and management, > Section 3.1.4.2 Separate Agreement and > Section 3.1.5.1 General ToR Aspects for the Implementation of an RMMV Approach.

After collection, the provided project location data is uploaded in a KfW-internal application called GeoApp within the Project Management Tool (PMT). Data entry in the GeoApp is easy and the application offers different options to link existing project data and activities to the provided location data (e.g., distribution of the project budget between the target provinces or districts). The data is securely stored and made available for internal use during the whole project cycle, where it can be combined with other internal and external data-sources to obtain a better impression of the local context. An example illustration below shows collected project location information based on the FC Project Location Model.

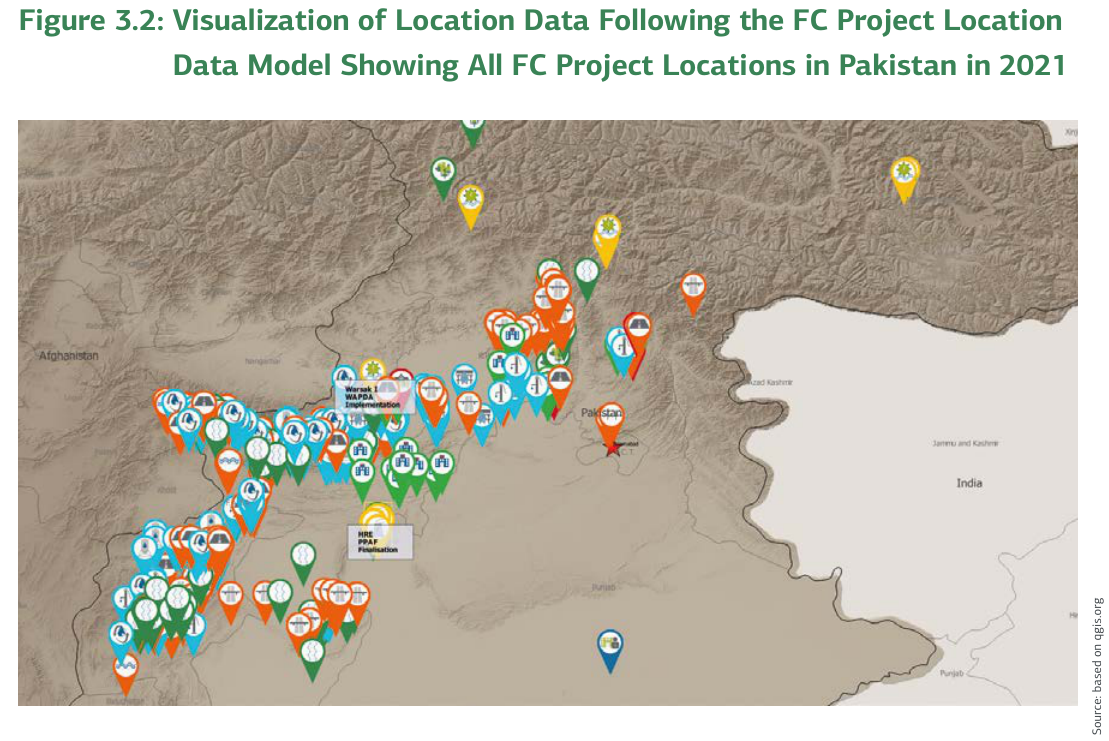

Figure 3.2: Visualization of Location Data Following the FC Project Location Data Model Showing All FC Project Locations in Pakistan in 2021

The above map shows all FC project locations under preparation and implementation in Pakistan in a uniform way.

Some of the locations are showing a selection of filter criteria (e.g., project title acronym, name of the PEA, implementation status of the location activity).

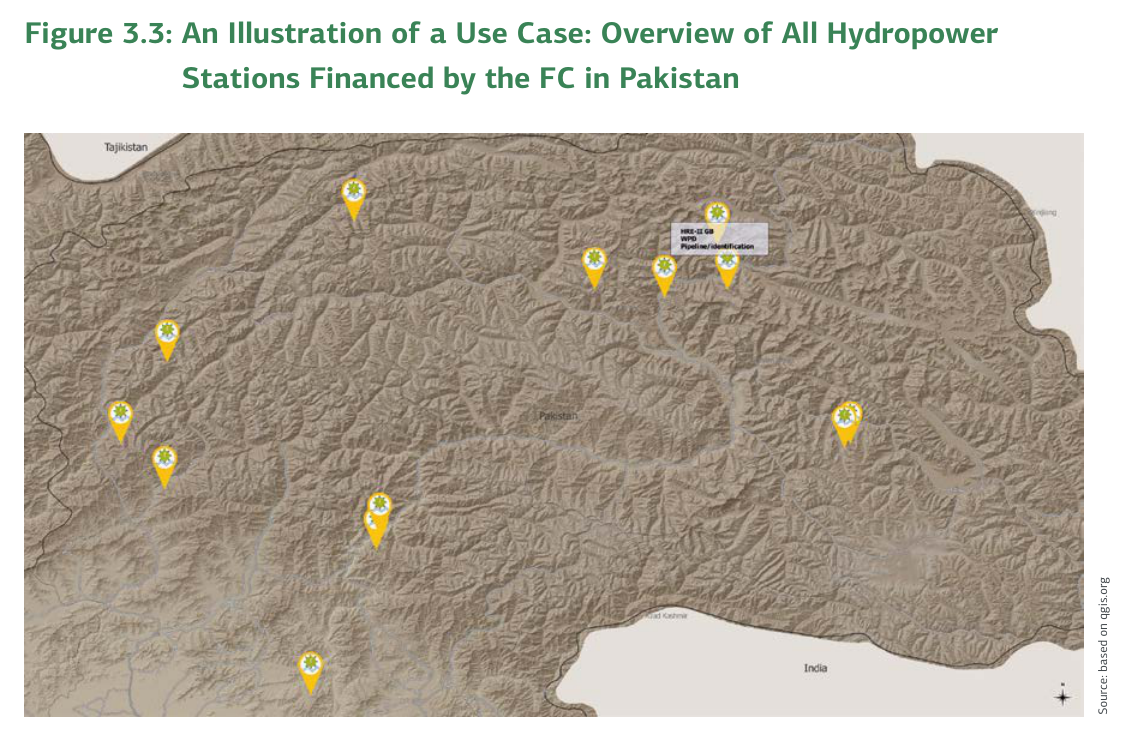

Now, all hydropower plant locations in Pakistan can be selected with one click:

Figure 3.3: An Illustration of a Use Case: Overview of All Hydropower Stations Financed by the FC in Pakistan

project. If different potential PEAs are considered, the organization's willingness may be a crucial selection factor. Therefore, the consultant must analyze whether the potential PEA(s) is/are willing to share relevant data, and which set(s) of institutional approaches and technical tool types they are or propose using.

- Analysis of PEA(s) experience and capacity with RMMV and proposed approaches: The consultant is to analyze the reliability of monitoring approaches and tools currently used by the PEA(s). If the PEA(s) already use(s) tools, the consultant is to assess whether these can be used or extended or additional tools or tool types are required. If the PEA uses a (Remote) Management Information System, see also, > Fact Sheet (Remote) Management Information System ToR Case B.

- Analysis of the local market for architects/planners and construction firms: If international and national firms cannot access the project sites, the project may have to rely on local planners and construction firms. In such cases, the consultant is to analyze whether there are local firms capable of and potentially willing to perform the required tasks.

- Analysis of the (local) market of monitoring consultants, IT experts and technical tool providers: the proposed set of RMMV approaches and tool types may require specific (local) expertise. How can this expertise be identified and engaged? Some tool types may be only accessible through certain public providers determined by the government (e.g., satellites or drones in some countries). How can these be procured? These issues need to be considered in the Feasibility Study.

This map of Pakistan shows the hydropower plant location, acronym of the project title "the respective project location is part of", "name of the PEA responsible for the project this location is part of" as well as the "implementation status of the main activity at the respective location".

The detailed FC Project Location Data Model and Management Approach, including the specific technical requirements, data collection ToR are presented in > Annex 3.

The same data collection Terms of Reference (ToR) have to be included as Sub-Annex to the Reporting Annex 8 of the project's Separate Agreement (> Section 3.1.4.2 Addressing RMMV in the Separate Agreement) as well as in the ToR of the respective consultant in charge of data collection, > Section 3.1.5.1 General ToR Aspects for the Implementation of an RMMV Approach.

3.1.2.4 Stakeholder Analysis and Incentive Model

As part of the Feasibility Study, project stakeholders and their respective positive and negative incentives are generally analyzed and incentive models for stakeholders are developed.

If RMMV approaches are to be used in the project, the analysis of such positive and negative incentives must include the following aspects:

- Target group analysis: if the target group is supposed to participate in the use of technical tools, the consultant must analyze local IT access conditions as well as the target groups' incentives as well as their actual IT-access disaggregated by gender, relative wealth, age, literacy (digital divide), relative remoteness (urban/rural divide) etc. to avoid unacceptably high levels of bias, and/or create awareness of bias considered acceptable or desired (e.g., bias towards youth in mobile feedback systems, which is underrepresented in traditional decision-making systems).

- Peace and Conflict Assessment: The Peace and Conflict Assessment is to propose methods for reliable Remote Monitoring of do-no-harm indicators and their assessment as to potential capacity gaps and conflicts of interest among the project stakeholders, forming the basis for the do-no-harm matrix (KFG-Matrix).

- Analysis of PEA willingness to appropriately use RMMV approaches: The PEA's willingness to use/ allow RMMV approaches appropriately is crucial to the success of a remotely managed and/or monitored

3.1.2.5 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment as Part of the Feasibility Phase

If RMMV approaches are to be used due to limited project site access, it must be clarified first, if potential environmental and social risk and impacts can be identified, whether these can be adequately assessed and subsequently managed and monitored via the applied RMMV approach or whether there are limitations or the project may even be unfeasible in a remote modality. Similarly, with regard to the aspects mentioned in the subsections above, the Feasibility Study consultant needs to analyze the possibilities and limitations of RMMV approaches for the a) identification and analysis of stakeholders and PAP, and b) socioeconomic baseline surveys, as well as census for resettlement and livelihood restoration.

Ideally the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) should be designed as an integral part of project design, such as in mainstreaming ESIA and ESMPs as part of participatory planning processes, or as a self-selection mechanism for small investment funds or programs (self-selection could for example result in exclusion of all proposals for sites where there have been any complaints by PAP).

The identification of environmental and social risks and impacts should be an integral part of the feasibility phase. Depending on the project type, scope and identified environmental and social risk category (A=high risk, B+=substantial risk, B=moderate risk and C=low risk), the Feasibility Study should include an assessment of environmental and social risks (for programs, an environmental and social framework is needed, as subprojects are not identified before appraisal). This should always include an E&S screening and scoping study or a section within the Feasibility Study. For high and substantial risks, an ESIA needs to be conducted within an independent document in the Feasibility Study phase by competent consultants as adequate preparation for the project appraisal. For moderate risk it has to be discussed whether an ESIA is needed or whether a site risk assessment, as part of the Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP), in the implementation phase is sufficient. The consultant needs to discuss with KfW and PEA whether and how RMMV approaches can be applied for the assessment of E&S aspects in the Feasibility Study phase.

For some risks related to category A and B+, the application of RMMV approaches may be limited and/or may involve challenges. In general, social aspects are more difficult to manage in a virtual environment. For example, applying RMMV approaches for World Bank ESS 5 on involuntary resettlement is challenging. Conducting socioeconomic baseline studies or census surveys for resettlement and livelihood restoration, including stakeholder engagement, may be difficult and require a tailored solution depending on the institutional approach used and on the technical RMMV tool types and data sources available, > Section 2.5 RMMV Decision Matrix. ESS 5 requires that the PAP be compensated before the impact materializes, thus there is a need for sufficient data to be available in a timely and reliable manner, while the compensation and livelihood restoration process needs to be implemented and monitored adequately as well. The same holds true for WB ESS 7 on indigenous people (IP), especially regarding the obtaining of the free prior informed consent (FPIC). In addition, one must be careful in applying RMMV approaches in the context of resettlement and IPs, as civil society actors view technical tools and approaches critically. Also, biodiversity baseline studies in natural or critical habitats may not be possible with all institutional approaches.

In addition, it needs to be clarified whether local consultants are available and competent enough to conduct screening, scoping and full-fledged ESIA (if required), whether or not guided by international experts. Many RMMV approaches feature a strong emphasis on consultants or even local consultants, thus the ToR for these assignments must be carefully developed and the consultants must demonstrate in their technical offer how they would apply RMMV approaches for each project task. For instance, it should be clarified which (satellite) data and tools they intend to use for what task. As an example: onsite bird flight monitoring in sensitive locations to determine if a given site is a critical habitat.

If in the pre-assessment considerable human rights risks are identified connected with the technical tool types you are planning to use, you may include a human rights risk assessment as part of your scoping or Feasibility Study. The Danish Institute for Human Rights provides useful guidance on > Human Rights Impact Assessment (HRIA) of Digital Activities, such as what to consider in the Terms of Reference for planning and scoping digital activities: > https://www.humanrights.dk/sites/humanrights.dk/files/media/document/Phase%201_Planning%20and%20 Scoping_ENG_accessible.pdf

If the technical tools you are planning to use for your project contain one or more of the following elements, you may consult the digital rights check developed jointly by KfW, GIZ and the Danish Institute for Human Rights: > https://digitalrights-check.bmz-digital.global/kfw/ and check the recommendations for the respective element(s) as well as the respective Tool Type Fact Sheets referenced below:

- Smartphone app > Fact Sheet Mobile Data Collection Tools

- eLearning tool > Fact Sheet eLearning Tools

- Internet-of-Things (IoT) device > Fact Sheet Sensors/Smart Meters

- Digital social or communications platform (incl. social media) > Fact Sheet Crowdsourcing Tools and > Fact Sheet Collaboration Tools

- Cloud services > Fact Sheet R/MIS and > Fact Sheet Data Sources

- Artificial intelligence solutions > Fact Sheet Data Sources

- FinTech solution > Fact Sheet Collaboration Tools

- Digital ID systems > Fact Sheet R/MIS and > Fact Sheet MMS

3.1.2.6 Local ICT Access Conditions

Local ICT access conditions must be assessed as part of the Feasibility Study because these are relevant for all tool types using mobile phones and a local internet connection. These may be mobile data collection tools, crowdsourcing tools, big data sources, R/MIS, Maintenance Management Systems, camera-based remote sensing, sensors or smart meters (internet-ofthings), > Tool Types Fact Sheets. Considering the precarious data situation in most partner countries, choices are often limited for the collection of accurate and representative data. The likelihood of reaching a near-representative or at least socially inclusive share of the population through mobile survey technology will increase along with rates of mobile phone penetration, household mobile phone ownership, the functional and ICT literacy of women and other vulnerable or marginalized groups, ICT affordability, and ICT connectivity. At least, the following topics are to be considered.

- Access to electricity: In Sub-Saharan Africa, some 600 million people (almost two-thirds of the region's population) do not have regular electricity, while 15% have no electricity access at all. 12 However, this however only severely limits mobile phone network access for people with no electricity access at all.

- Mobile phone ownership: In 2024, 5.61 billion people worldwide used a mobile phone (equaling 69.4% network access, of which an estimated half are smartphones). 13 However, Asian-Pacific and African countries in particular lag behind. While the percentage of smartphone use is increasing (by the end of 2020, over 4 billion people were using mobile internet, representing 51% of the world's population) 14, poor and rural populations in particular only have access to simple mobile phones without broadband access or the advanced computing functions of a smartphone. Currently, cross-national data sets on mobile phone penetration, such as provided by the World Bank, are based on estimations of the number of cellular subscriptions. However, this may not accurately reflect penetration (i.e., the percentage of phone owners among the population), as one person may own multiple mobile phones. An increasing but still limited number of national statistical institutes of developing countries are providing more accurate information on mobile phone ownership.

- Access to internet: Basic access to broadband internet is available in every capital and larger city around the world, but rural communities are often excluded. In January 2024, 5.35 billion people use the internet (66%). 15 Merely 45.5% of people in Africa have access to the internet today though 16, and current growth trends suggest we will be well into the second half of the 2020s before we see internet access levels across the continent pass the 50% mark. Broadband access rates are even worse, especially in remote and rural areas. In many countries, broadband internet is quite expensive. High prices may exclude poor people from usage, even when network access is available.

- Network infrastructure: One common reason why people do not access the internet is poor mobile network infrastructure. For projects where mobile phones needed to transfer data, it is recommended to use a mobile operator with at least 3G net coverage, otherwise long waiting times may occur. 3G net coverage is given in most countries in the world, but the available net coverage differs regionally. 4G coverage had increased to 84% in lower-middle-income countries (LMIC) by the end of 2020.

- Usage gap: Even though the coverage gap has narrowed in recent years (see above), there is still a huge gap in usage. In 2022, 38% or 3 billion people did not use mobile internet despite living in areas with mobile broadband coverage. 17

- Gender gap: There is also a sobering gender gap online. In developing countries, the parity between male and female internet users can be startling. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the gender gap can range from 10-62%. 18 Women in low and middle-income countries are, on average, 17% less likely to own a mobile phone than men, and 19% less likely to use mobile internet. 19 The gender gap is significantly lower in urban than in rural areas, and for younger versus older women. In addition to mobile phone access, there is also a gender gap regarding phone use due to illiteracy, functional literacy or limitation to the local language (as opposed to the official language), which must be considered.

- National ICT expertise: Moreover, the existence of progressive and pro-competitive regulatory ICT-policy frameworks and national ICT R&D funds are usually associated with higher levels of in-country ICT expertise. This, in turn, would be an enabling factor for realization of the technical infrastructure for the project. National ICT experts will likely be better qualified to develop software solutions that are suited to the specific local context and to sustainably maintain the necessary hardware than external international consultants. During the Feasibility Study, to gain a better understanding of the telecommunications environment we recommend consulting the following sources to analyze the local ICT access conditions:

- International Tele-Communication Union: ICT Development Index > https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/IDI/default.aspx;

- Alliance for affordable internet: Affordability Report > https://a4ai.org/research/affordability-report/ affordability-report-2021/;

- GSMA: Mobile Connectivity Index > https://www.mobileconnectivityindex.com/ and > https://www.gsma. com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/connected-women/, and > https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/external-affairs/

- Internet World Stats (offers statistical indicators about internet usage for every country) > https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS.

Solutions should be adapted to local energy and ICT access conditions, but adaptations may be possible. For example, electricity can be provided through solar panels. If the network signal is too weak to transfer data immediately, mobile phones can be used as buffer memory and the data can be transferred later when there is better net coverage. Camera and UAV/drone-based sensors can load data onto a data storage device which can then be manually read at regular intervals.

12 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31333/9781464813610.pdf?seq and https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 13 https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2024/01/digital-2024/ 14 https://www.gsma.com/r/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/The-State-of-Mobile-Internet-Connectivity-Report-2021.pdf

15 https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2024/01/digital-2024 16 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1318881/internet-usage-rate-in-africa-by-gender/ 17 https://www.gsma.com/r/somic/ 18 https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2024/ 19 https://www.gsma.com/r/somic/

3.1.2.7 Implications of Using RMMV Regarding Project Cost and Duration

RMMV may have different effects on project cost and duration that should be taken into consideration when assessing project feasibility and drafting the project budget and time schedule outline as part of the Feasibility Study. The implications are discussed in this Section.

Cost and resource implications at KfW-level At KfW-level, transaction cost may increase. Remote Management and Verification of projects may be more expensive than regular project management and verification. Even though international staff may spend less time traveling, remote project management and Remote Verification imply greater workload. Portfolio managers may have to recruit and manage additional consultants, including preparations for their missions, managing their contracts and addressing findings after the mission. If KfW national experts take more responsibility, for example, in supporting Remote Verification and coordination among KfW staff, partners and stakeholders , they must be trained and coached by international KfW staff. Finally, communication with the PEA may take more time and require more rescheduling and troubleshooting effort in the absence of a possibility to hold clarifying meetings during a mission.

Cost implications at project-level At project-level, cost implications depend on the institutional RMMV approach(es), tool types and data sources chosen > Section 2 RMMV Approaches and Tools - an Overview. Some empirical data indicative of the cost implications of different institutional approaches is available (> Section 2.1 for a discussion of institutional approaches):

- The cost implications of an Implementation Consultant with increased local capacity (> Section 2.1.1, A3) may vary: while increasing reliance on local staff may be cheaper, the cost of training and supervising them may be significantly greater, as well as security and flight costs (for intermittent trips by international staff). For some projects relying strongly on RMMV because of conflict-related site access issues, consulting cost has tripled.

- Costs for monitoring consultants depend on the range of services they provide (> Section 2.1.1, A2 and A3): In general, monitoring consultants have the same monthly rates as Implementation Consultants. However, the range of services demanded of monitoring consultants can differ substantially. If monitoring consultants have a limited mandate, they may only cost a small fraction of the total project volume. The more implementation responsibility the consultant takes on, the more expensive it gets.

- Third-party monitoring consultants are relatively affordable (> Section 2.1.1, A4). Usually they also cost a small fraction (1 to 5%) of the total project volume, assuming that only a sample of outputs and/or outcomes is monitored. It must be considered however that frequently a TPM consultant is recruited in addition to an Implementation Consultant, which increases overhead cost.

- Third-party monitoring through technical audit is even more affordable (> Section 2.1.1, A4): this approach, used for example in a KfW-financed project in Yemen, was estimated to cost less than 1% of the overall project sum. This was of course also due to its limited scope.

The cost of hiring additional national technical experts at KfW country office level is not included in the project budget, as they are tasked with conducting KfW Remote Verification activities and usually cover KfW's entire sector portfolio in the country (> Section 2.1.1, A1).

For technical tools, cost is not the main selection criterion, and it is also more difficult to estimate their cost implications, as these include software, hardware, training, promotion activities, etc. However, some empirical data is available:

- Hardware and data can come at relatively low cost. Examples of this are socioeconomic databases (mostly open and free), satellite-based remote sensing (usually less than EUR 10 per image per sqm) and camera-based remote sensing (a 360-degree camera can cost between EUR 150 and EUR 1,000) and intelligent sensing (sensors cost can vary between EUR 1 and EUR 500 per unit).

- Standard monitoring or data analysis and visualization tools can be significantly cheaper if existing (open) data sources are initially or from periodically combined with project-generated data through a data dashboard solution (e.g., Power BI, Tableau etc.).

- Software development services and software licensing fees can be relatively expensive. The original development of a proprietary remote project management information system did cost about EUR 120,000 in 2018 in addition to annual licensing fees. If open-source software is used, these costs can be substantially lower. Adaptation of the open-source Rapidpro software for the citizen monitoring project in Togo was only a fraction, without any licensing fees, > Decentralization Support Program in Togo (PN: 30205).

- Other cost items required for technical tool types also need to be considered. These include IT equipment (computers, smartphones, servers), training on software development, content management and/or user training, promotion and social mobilization activities, subsidizing of short message service (SMS) fees (e.g., for mobile data collection or crowdsourcing) and regular updates and maintenance.

Implications of RMMV for Project Duration Implications regarding duration depend on the selected institutional approach as well as the software requirements for the selected technical tool(s):

- Setting up a Remote Management Information System (R/MIS) takes time. If software crucial for progress monitoring needs to be developed or adapted, this can delay the start of construction works in a project. Software development usually requires a sequence of programming and feedback from users. This process may take up to six months and delay project start. Therefore it should be part of the ToR of the Implementation Consultant (or additional IT consultant), and start in parallel with the planning stage or be procured by the PEA parallel to the procurement of the Implementation Consultant (as done in the > Stabilization Program M-naka, Mali, (PN: 38771).

- Deployment of UAV/drones may also take time. Drones frequently need to be imported and may be stuck at customs. Furthermore, obtaining the necessary permits to operate the drone may take additional time.

3.1.2.8 Considerations on Designing KfW's Remote Verification Approach

If due to the security situation or other project-specific circumstances the physical verification steps (appraisal, progress and final review, including the verification of the use of funds as well as ex post evaluation) are not possible or cannot be carried out by KfW itself wholly or in part, this must already be taken into account in the Feasibility Study if such a risk has already been identified at that stage. In such case, all these steps have to be conducted using the RMMV approach (choice of institutional approaches as well as types of technical tools and data sources) in accordance with > Section 2, in particular > Section 2.5 RMMV Decision Matrix as well as > Section 3.3 Remote Verification of Project Progress by KfW. In designing the RMMV approach as part of the Feasibility Study, the expected reporting from the Remote Monitoring of project implementation is considered (> Section 3.2 Project Implementation and Monitoring by The PEA/Consultant) and combined with additional, independent sources of information. The RMMV approach design is then agreed in the contractual setup for procuring technical tool types, > Section 3.1.5.1 General ToR Aspects for the Implementation of an RMMV Approach.

If adequate Remote Verification procedures cannot be identified, the feasibility of the project needs to be discussed with the respective KfW client for the project, > Section 1.5.1 Limitations.

3.1.3 Conducting Project Appraisals Remotely

It is important to consider RMMV in this step within the FC project cycle because it constitutes the first verification process for KfW, enabling KfW to verify the results of the Feasibility Study. Furthermore, crucial elements of the project, including the relevant mix of institutional approaches and tool types, are defined with the PEA in the appraisal, and KfW's client is informed of the chosen RMMV approach and related RMMV risks.

Please note that this Section does not outline guidelines for the general KfW project appraisal process but rather only discusses additional aspects that should be considered when conducting project appraisals remotely.

If due to the security situation or other specific circumstances of the project a physical appraisal mission is not possible or cannot be carried out by KfW itself, wholly or in part, this must already be taken into account in the project planning phase if such a risk has already been identified at that stage. In such case, remote appraisal has to be conducted using the RMMV approach (choice of institutional approaches as well as types of technical tools and data sources) in accordance with Section 2, in particular > Section 2.5 RMMV Decision Matrix as well as the sections below. The proposed RMMV approach should already be stated in the appraisal concept and discussed during the appraisal peer review.

If adequate Remote Verification procedures are not available, the feasibility of the project needs to be discussed with the respective client of KfW for the project, > Section 1.5.1 Limitations.

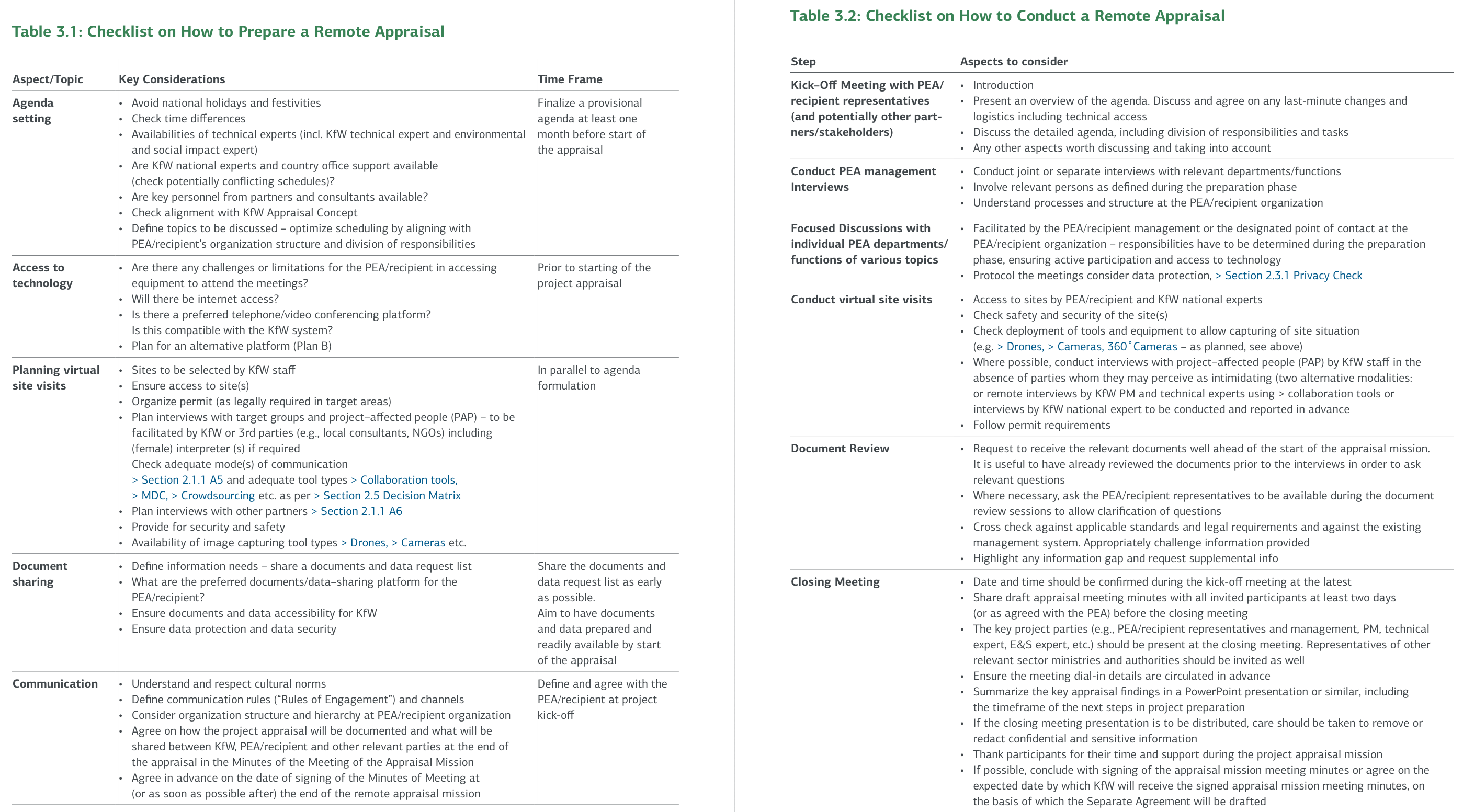

3.1.3.1 Preparation of Remote Appraisals

A well-designed appraisal concept is necessary to successfully conduct a project appraisal remotely. Sufficient time should be reserved for the preparation of a remote appraisal mission to ensure an optimized process and efficient data collection. The PM has responsibility for coordination and ensuring that the appraisal is well planned. External inputs are essential to the success of a project appraisal, thus it is recommended to involve the relevant parties (in particular the relevant PEA, recipient government and target groups representatives, as well as other partners and stakeholders) as early as possible, and to ensure their availability and access to the required IT-infrastructure. Frequently, additional data needs to be collected in advance of the remote appraisal mission which otherwise would have been collected on site during the mission.

The following should be considered and planned for in coordination with the PEA/recipient:

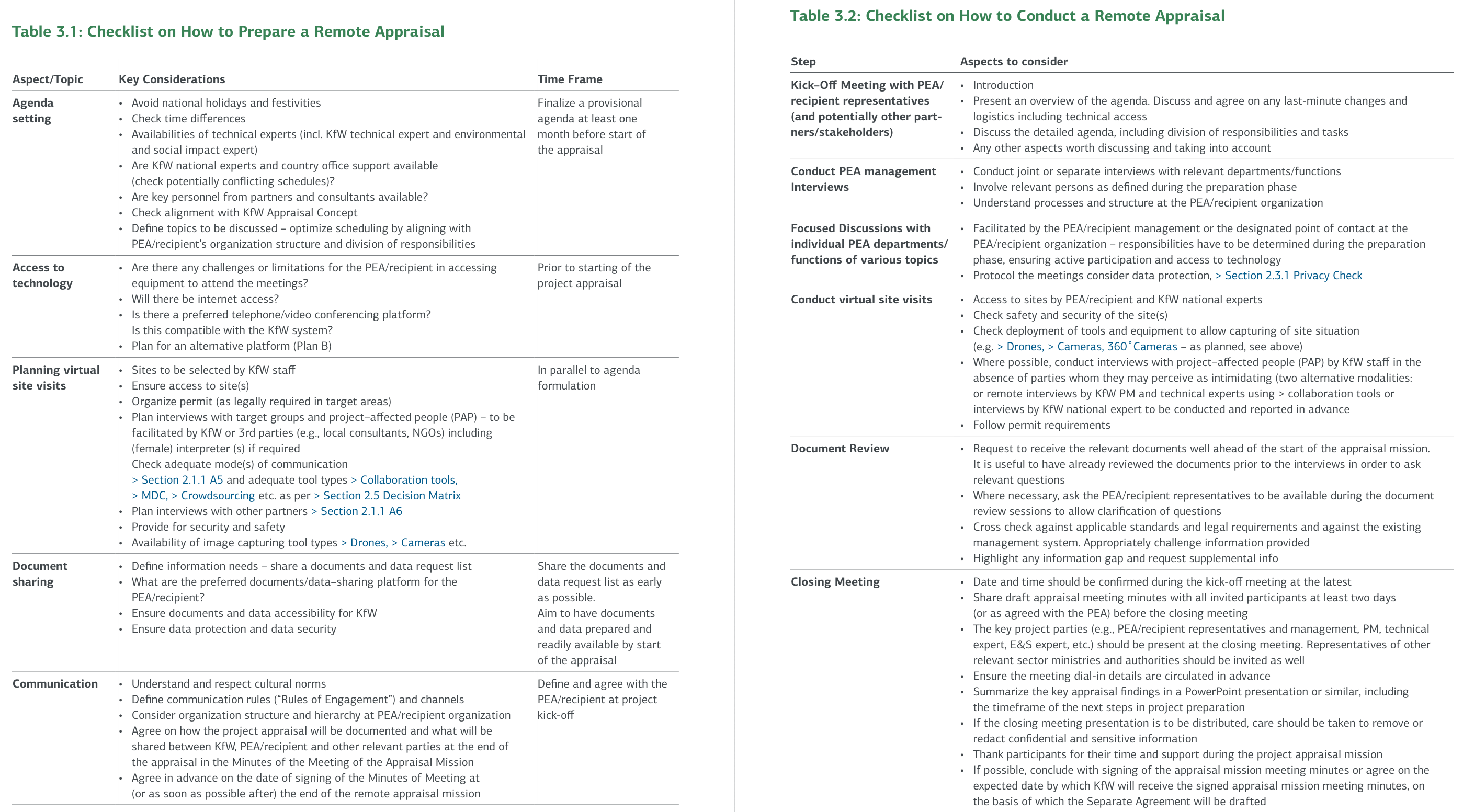

Table 3.1: Checklist on How to Prepare a Remote Appraisal

3.1.3.2 Conducting Virtual Appraisal Missions

A Virtual Appraisal Mission is likely to take place over a series of telephone/video conferences and involve accessing of technical tool types and data sources, depending on the setup as determined during the preparation phase. The approach should allow a level of flexibility, and potentially for the participation of additional technical experts. However, a high level of coordination is required to ensure efficient use of time and that the information obtained reflects as accurately as possible the likely risks and impacts of the project. It is therefore recommended to confirm the appraisal agenda with the PEA/recipient at least two weeks prior to start of the project appraisal as well as other logistical aspects mentioned above.

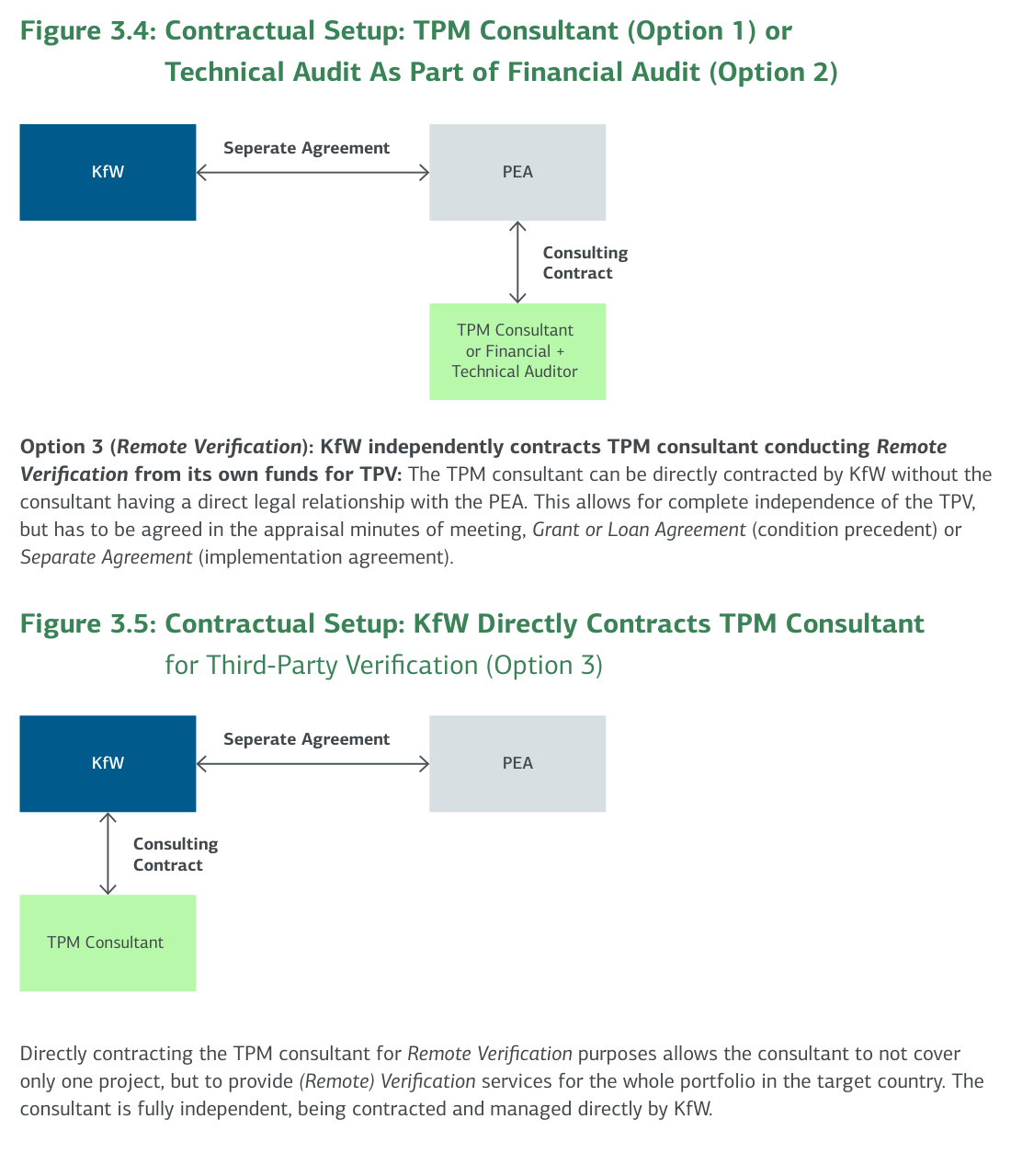

The following illustrates the process of conducting a typical virtual project appraisal and aspects to be considered:

Table 3.2: Checklist on How to Conduct a Remote Appraisal

Step Aspects to consider

Aspect/Topic Key Considerations Time Frame

Kick-Off Meeting with PEA/

- Introduction Agenda setting Access to technology

- Avoid national holidays and festivities

- Check time differences

- Availabilities of technical experts (incl. KfW technical expert and environmental and social impact expert)

- Are KfW national experts and country office support available (check potentially conflicting schedules)?

- Are key personnel from partners and consultants available?

- Check alignment with KfW Appraisal Concept

- Define topics to be discussed - optimize scheduling by aligning with PEA/recipient's organization structure and division of responsibilities

- Are there any challenges or limitations for the PEA/recipient in accessing equipment to attend the meetings?

Finalize a provisional agenda at least one month before start of the appraisal

Prior to starting of the project appraisal

recipient representatives (and potentially other partners/stakeholders)

Conduct PEA management Interviews

Focused Discussions with individual PEA departments/ functions of various topics

- Present an overview of the agenda. Discuss and agree on any last-minute changes and logistics including technical access

- Discuss the detailed agenda, including division of responsibilities and tasks

- Any other aspects worth discussing and taking into account

- Conduct joint or separate interviews with relevant departments/functions

- Involve relevant persons as defined during the preparation phase

- Understand processes and structure at the PEA/recipient organization

- Facilitated by the PEA/recipient management or the designated point of contact at the PEA/recipient organization - responsibilities have to be determined during the preparation phase, ensuring active participation and access to technology

- Protocol the meetings consider data protection, > Section 2.3.1 Privacy Check Planning virtual site visits Document sharing

- Will there be internet access?

- Is there a preferred telephone/video conferencing platform? Is this compatible with the KfW system?

- Plan for an alternative platform (Plan B)

- Sites to be selected by KfW staff

- Ensure access to site(s)

- Organize permit (as legally required in target areas)

- Plan interviews with target groups and project-affected people (PAP) - to be facilitated by KfW or 3rd parties (e.g., local consultants, NGOs) including (female) interpreter (s) if required Check adequate mode(s) of communication > Section 2.1.1 A5 and adequate tool types > Collaboration tools, > MDC, > Crowdsourcing etc. as per > Section 2.5 Decision Matrix

- Plan interviews with other partners > Section 2.1.1 A6

- Provide for security and safety

- Availability of image capturing tool types > Drones, > Cameras etc.

- Define information needs - share a documents and data request list

- What are the preferred documents/data-sharing platform for the PEA/recipient?

- Ensure documents and data accessibility for KfW

- Ensure data protection and data security

In parallel to agenda formulation

Share the documents and data request list as early as possible. Aim to have documents and data prepared and readily available by start of the appraisal Conduct virtual site visits

- Access to sites by PEA/recipient and KfW national experts

- Check safety and security of the site(s)

- Check deployment of tools and equipment to allow capturing of site situation (e.g. > Drones, > Cameras, 360?Cameras - as planned, see above)

- Where possible, conduct interviews with project-affected people (PAP) by KfW staff in the absence of parties whom they may perceive as intimidating (two alternative modalities: or remote interviews by KfW PM and technical experts using > collaboration tools or interviews by KfW national expert to be conducted and reported in advance

- Follow permit requirements Document Review

- Request to receive the relevant documents well ahead of the start of the appraisal mission. It is useful to have already reviewed the documents prior to the interviews in order to ask relevant questions

- Where necessary, ask the PEA/recipient representatives to be available during the document review sessions to allow clarification of questions

- Cross check against applicable standards and legal requirements and against the existing management system. Appropriately challenge information provided

- Highlight any information gap and request supplemental info Closing Meeting

- Date and time should be confirmed during the kick-off meeting at the latest

- Share draft appraisal meeting minutes with all invited participants at least two days (or as agreed with the PEA) before the closing meeting

- The key project parties (e.g., PEA/recipient representatives and management, PM, technical expert, E&S expert, etc.) should be present at the closing meeting. Representatives of other relevant sector ministries and authorities should be invited as well Communication

- Understand and respect cultural norms

- Define communication rules ("Rules of Engagement") and channels

- Consider organization structure and hierarchy at PEA/recipient organization

- Agree on how the project appraisal will be documented and what will be shared between KfW, PEA/recipient and other relevant parties at the end of the appraisal in the Minutes of the Meeting of the Appraisal Mission

- Agree in advance on the date of signing of the Minutes of Meeting at (or as soon as possible after) the end of the remote appraisal mission Define and agree with the PEA/recipient at project kick-off

- Ensure the meeting dial-in details are circulated in advance

- Summarize the key appraisal findings in a PowerPoint presentation or similar, including the timeframe of the next steps in project preparation

- If the closing meeting presentation is to be distributed, care should be taken to remove or redact confidential and sensitive information

- Thank participants for their time and support during the project appraisal mission

- If possible, conclude with signing of the appraisal mission meeting minutes or agree on the expected date by which KfW will receive the signed appraisal mission meeting minutes, on the basis of which the Separate Agreement will be drafted

3.1.3.3 Environmental and Social Considerations of Virtual Appraisal Missions

In general, the pre-appraisal phase consists of a desktop review of the conducted studies (Feasibility Study, ESIA, etc.) and discussions with consultants and partners on open issues. A list of open questions should be sent to the partner before the appraisal mission so they can prepare for the appraisal mission. Based on the conducted studies, it is also good practice-required-to develop a draft version of the Environmental and Social Commitment Plan (ESCP) before the appraisal mission and send the draft to the partners for discussion during the mission. In addition, we recommend using the KfW > Digital Rights Check before or during the appraisal mission, if you need to identify and mitigation potential human rights risks from the use of RMMV tools or other digital technologies within the project.

This approach is also feasible for virtual appraisal missions. Physical presence in the country and/or project region is not possible in this case, so the meetings and/or site visit have to be conducted virtually. It is good practice to prepare the virtual appraisal as diligently as one would a "normal" appraisal, with a clear agenda and stating exactly who has to be present at which meetings. For instance, the E&S team of the partner and KfW obviously have to be present at the meetings on environmental and social topics, but the KfW project team needs to analyze and discuss at what further sessions the E&S staff need to be included, as it is vital to include them in the sessions on the project Implementation Consultant or the procurement documents, for example (as there are relevant ESHS requirements which need to be discussed).

Virtual site visits can be conducted via web conferencing, image-assisted site assessment, 360?/helm mounted cameras, etc., see Fact Sheets on > Collaboration Tools, > Mobile Data Collection Tools, and > Cameras.

Virtual meetings with communities/PAPs may be difficult, but at least interviews with PAPs can be conducted using a mobile phone with camera and streamed within a web conferencing tool, > Collaboration Tools.

Ad-hoc discussions with stakeholders are difficult to do, and triangulation of information by interviewing stakeholders randomly is difficult as well. But if the security situation allows, KfW national experts can be present in the project area before or during the appraisal mission and can interview stakeholders randomly chosen by KfW from a list made available by the Feasibility Study consultant or PEA.

Virtual Meetings with PAPs without project partners would be a possibility to get unfiltered information for unbiased opinions, but this requires that partner institutions' staff are not involved in the interviews,being organized and conducted for example by KfW national experts. It is additionally important that the PAPs/ communities are randomly chosen by KfW (e.g., from the list of PAPs from the resettlement action plan) for such virtual interviews, and are not proposed/selected by the project partners.

Similarly, any necessary meetings with NGOs or workers unions must be organized and it must be clarified in advance whether those meetings are to be done with or without the presence of partner institutions. Interpreters are required in any case. Finally, care must be taken, that the integrity of interviewed PAPs is assured.

3.1.4 Contractual Considerations

To ensure the successful implementation of a RMMV-strategy it is imperative that the key underlying project agreements (Grant or Loan Agreement, Separate Agreement and consultancy contract(s)) clearly regulate the RMMV-related rights and obligations of the respective parties in a legally binding way.

3.1.4.1 Addressing Crucial RMMV Prerequisites in the Grant or Loan Agreement

In rare cases, if RMMV-related prerequisites have been identified during project preparation are so crucial for the success of the project that it would otherwise fail, or KfW cannot other verify the use of funds, those prerequisite(s) should be agreed during the course of the government negotiations (> Section 3.1.1 Government Negotiations) or during the project appraisal mission (> Section 3.1.3 Conducting Project Appraisals remotely). In such cases, and given the importance of such prerequisites, it may be appropriate to include these in the respective Grant or Loan Agreement (e.g., as undertakings, covenants or conditions precedent to disbursement). One example for such a prerequisite is the need to ensure access by KfW or the respective third party to necessary information from a partner's R/MIS. If this is considered uncertain or if there is a risk of potential RMMV-related human rights issues (e.g., data protection provisions in citizen feedback loops or use of AI-assisted big data), consideration in the a.m. agreements is strongly recommended.

The issues/prerequisites have to be identified (e.g., in the Feasibility Study) and discussed at an early stage (ideally at the project preparation kickoff-meeting) with the KfW contract manager and/or the KfW legal team to clarify what changes if any will have to be made to the relevant Grant or Loan Agreement template 20, and which will therefore have to be included in the Project Proposal as an implementation condition requiring the approval of the BMZ.