1. Introduction to Remote Management, Monitoring, and Verification

1.1 KfW’s Mandate and Role in German Development Cooperation

KfW is one of the world’s leading development banks and has been committed to improving economic, social, and environmental living conditions across the globe on behalf of the Federal Republic of Germany and the federal states since 1948. In this regard, KfW is both an experienced bank and a development institution with financing expertise, expert knowledge of development policy, and many years of national and international experience. On behalf of the German Federal Government, and primarily the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), its main client, KfW finances and supports programs and projects that mainly involve public–sector players in developing countries and emerging economies—from their conception and implementation to monitoring their success.

KfW’s goal is to help partner countries fight poverty, maintain peace, protect both the environment and the climate, and shape globalization in an appropriate way.1

KfW Development Bank supports projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Latin America, and SouthEast Europe. In this way, KfW is continually building its global presence to ensure close cooperation with its partners. In addition to KfW’s offices in Frankfurt, Berlin, and Brussels, the institution has offices in almost 70 countries. The spectrum of projects promoted ranges from investments in large-scale infrastructure—for example, renewables, urban transport systems, water supply, and wastewater disposal—to national credit lines for smalland medium-sized enterprises, and the development of basic social services. In addition to the direct impact of the individual projects, it also often initiates structural reforms to contribute to sustainable development on a permanent basis.

To do this, KfW Development Bank committed EUR 9 billion in new financing in 2021 alone. Its financing and promotional services are aligned with the United Nations’ Agenda 2030 and contribute to the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

KfW receives part of its funding for development projects and programs from the German federal budget. In 2021, this figure amounted to about EUR 3.6 billion. KfW also uses funds received from other public-sector clients, such as the European Union (abou EUR 400 million in 2021) or those raised on the capital markets, which are referred to as KfW Funds. In 2021, KfW Funds totaled about EUR 4.6 billion. This allows KfW to multiply the impact of the public budget funds used.2

KfW’s funding instruments include pure, non-repayable financial contributions, loans from budget funds (standard loans), loans financed by KfW with interest subsidized by grants from the German Federal Government (development loans), loans financed by KfW at near-market conditions (promotional loans), and equity participation. In poor and underdeveloped countries, KfW mainly uses financial contributions and budget-funded standard loans, which are offered on soft terms. A large proportion of these (51%) went to Africa and Asia in 2021. KfW uses development and promotional loans in advanced developing countries and emerging economies for projects that are both useful from a development policy perspective and economically profitable. The partner countries benefit from the favorable refinancing conditions obtained by KfW because of its AAA rating, the subsidizing of interest partly by using German Federal Government funds, and the partial assumption of risk by the German Federal Government.

The projects and programs promoted by KfW Development Bank are proposed by the governments of its partner countries. The respective country's development strategies and structures form the basis. On behalf of the German Federal Government, and primarily BMZ, KfW checks whether the projects and programs are developmentally sound and eligible for funding. The promoted projects and programs are proposed during bilateral government negotiations and the German Federal Government decides on the maximum amount of financial funds to be committed. An intergovernmental agreement is generally concluded on this matter. KfW's experts assist partners in any way they can and support projects for their duration.

Working together with the partner, specialized consulting firms draw up a Feasibility Study, which provides answers to all of the project's key questions—economic efficiency, developmental impacts and possible risks.

Social, cultural, and ecological aspects are taken into account. Once all of the preparatory measures have been taken, the KfW Development Bank concludes a Grant or Loan Agreement including a Separate Agreement with the PEA. For example, the Separate Agreement may specify what must be observed when building a hydropower station or school, or how the operating costs are being covered. The PEA is responsible for the project itself. It puts goods and services out to tender and monitors the building phases. KfW PMs assist clients during these steps and provide the German Federal Government with regular progress reports.

Following completion, KfW closely examines the project during the final review. The aim here is to determine whether productivity levels are being reached, the specifications have been complied with, and the funds have been used as planned. KfW has an independent evaluation department that assesses whether projects and programs have achieved lasting success. About five years after completion, the KfW ex-post evaluation department takes samples of completed projects and programs, analyzes the impacts achieved, evaluates the costs, and compares the results. In the long term, the development bank's projects and programs have an average success rate of about 80%.

The type of funding KfW opts for depends on the size of a country’s debt, its economic output, and level of development, the performance capacity of the project partner, and the type of project or program in question.

1.2 What is RMMV from a KfW Perspective?

Remote Management, Monitoring, and Verification (RMMV) is a framework developed by KfW Development Bank. It describes the challenges that arise for stakeholders of KfW-financed projects if they cannot travel to (all) project sites and offers a methodology, institutional approaches, and practical advice on how to overcome them.

The use of RMMV requires new methods for KfW and its project partners, especially PEAs and consultants. To describe them, the distribution of roles and responsibilities typical for Financial Cooperation (FC)—i.e., KfW’s limited involvement in project execution—was used as a starting point, resulting in the following key definitions; for more details:

“Remote Management” is the overarching framework for developing and managing projects/portfolios based on the information gathered through Remote Monitoring and Verification (and potentially remote country office management). Remote Management refers to the management of development projects remotely, that is, without the ability of the project managing entity to be physically where the activity is carried out. This includes remote site supervision in projects involving infrastructure construction and remote country office management where no international staff (including the country office director) can enter the country.

As part of Remote Management, stakeholders responsible for the implementation of activities might also have to apply “Remote Monitoring” of costs, cash flow and financing, progress, as well as Remote Monitoring of outputs, outcomes, and/or positive or negative impacts, including social and environmental impacts by substitute actors (e.g., local instead of international staff) and/or technical tools (e.g., satellites and smartphones). In KfW-financed projects, Remote Monitoring is usually the task of the PEA and/or a consulting company designated as the “Implementation Consultant.”

In this framework, KfW portfolio management and technical staff are tasked with verifying the reported information and/or project activities. Should they be unable to conduct such a verification in the location in which the activity is carried out, “Remote Verification,” which can involve substitute actors and/or technical tools, by comparing information from different sources and/or verifying the quality and coherence of large data sets is used.

Remote Verification is KfW’s core task for verifying the available information while conducting remote project appraisals, final inspections, and ex–post evaluations. During project execution, Remote Verification is used to remotely control progress and the correct use of funds, compliance with KfW quality standards, and verify project monitoring reporting. This is especially necessary in highly fragile or corrupt environments with weak partners;

- for a full glossary of relevant terms. In the implementation phase, the partner country’s PEA is usually responsible for all activities—executing the project and monitoring outputs and outcomes. Sometimes, an Implementation Consultant may also take over some or most Remote Management and Monitoring roles of the PEA. During this time, KfW only verifies project progress, the use of funds, and project completion by special missions of staff from KfW headquarters to project locations in the partner country. So, in fact, for the largest part of the project cycle—during project implementation—KfW already works mostly remotely.

However, the following processes change when RMMV is applied:

- KfW international staff also works remotely for project appraisal, verification of project progress and completion, and impact evaluation.

- Consultants supporting KfW and the PEA during project preparation may not be able to visit project sites and project stakeholders

- The PEA and the Implementation Consultant may also have limited access to the site. In some contexts, even qualified national staff or any staff not from the specific village or town where project sites are located may not be able to visit the sites.

1.3 KfW’s Expectations vis-à-vis RMMV

RMMV approaches are expected to enable KfW to continue providing its standard functions even when KfW international staff cannot visit the country and/or (all) the project location(s). KfW has used RMMV approaches when working in areas where it is too dangerous to travel, such as in conflict environments and areas affected by natural disasters. There are also instances where the distance between project sites makes it difficult to complete work in a timely fashion. The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced new challenges. Travel restrictions, lockdowns, and quarantines have made areas that were once routinely safe to work in and easy to reach, extremely difficult or impossible to work in, requiring KfW staff and consultants to work from a distance on a routine basis. KfW portfolio management and technical experts need sufficient information to prepare and appraise projects. During implementation, they need to identify undesirable developments early on, so that they can counteract them in time. For this purpose, decisive influencing factors, such as the schedule, cost, impacts, and risks must be observed regularly.

Furthermore, KfW must verify project progress and completion and the correct use of funds and provide regular reporting to its client, the German government represented by its ministries, for example, BMZ. Overall, RMMV is being used to enable KfW to obtain some of the following information—depending on the respective information needs of the projects:

- information on the project context allowing target area and target groups selection

- target group baseline information and needs

- target area baseline information

- construction/works progress and quality (to the extent feasible) or other project progress data

- level of usage of the infrastructure/service(s) financed by KfW

- environmental/climate impact of the project

- social impact, including do-no-harm monitoring of the project

- use of funds disbursed by KfW

- operation and maintenance of the infrastructure/service(s) financed by KfW

- target group and other stakeholder feedback on the project

- target groups’ level of satisfaction with the project

- sector development and project impact

- communication with the PEA, ministries, donors, other partners, and stakeholders

In international development, expectations about quality standards or sustainability have sometimes been reduced in projects in fragile contexts with access constraints that heavily rely on RMMV. Judging from the indicators used by such projects and the quality of reporting, project outcomes and impacts are sometimes only approximated, if measured at all. Furthermore, higher risks, such as lower construction quality and higher sustainability risks (less monitoring of operations and maintenance) have often been accepted.

RMMV needs to ensure that KfW and its project partners can not only gather information for management, implementation, monitoring, and verification but also can assess the quality of this information and consider different perspectives to reach acceptable and sustainable project outcomes and impacts even in highrisk environments.

This requires different types of triangulation: KfW’s Expectations vis-à-vis RMMV triangulation of methods and types of information (e.g., verify quantitative indicators through qualitative information); triangulation of stakeholder perspectives (e.g., asking the PEA, target groups, and third parties about the same situation); and triangulation of investigator/consultant (e.g. asking the PEA whether information provided by a consultant in a Feasibility Study is correct).

Box 2: Six Principles to Assess Information Quality Information reliability:

Will we get the same data when we collect again?

Information validity:

Are we measuring what we say we are measuring?

Information integrity:

Is the information free of manipulation?

Information accuracy/precision:

Is the data measuring the indicator accurate?

Information timeliness:

Is the information recent and does it arrive on time?

Information security/confidentiality:

Is loss of information/loss of privacy prevented?

Source: joyn-coop based on Shukla and Sen, 2014,

- List of Literature

The COVID-19 pandemic has also introduced new opportunities and related expectations: the pandemic-induced proliferation of online videoconferencing and related tools, for instance, made the inclusion of target group representatives in project steering committee meetings possible. It was not possible to include these representatives in personal meetings at the PEA level in the past. This can considerably help in building trust and improving collaboration among all project parties.

1.4 The Principles for Digital Development Applied to RMMV

The Principles for Digital Development Applied to RMMV

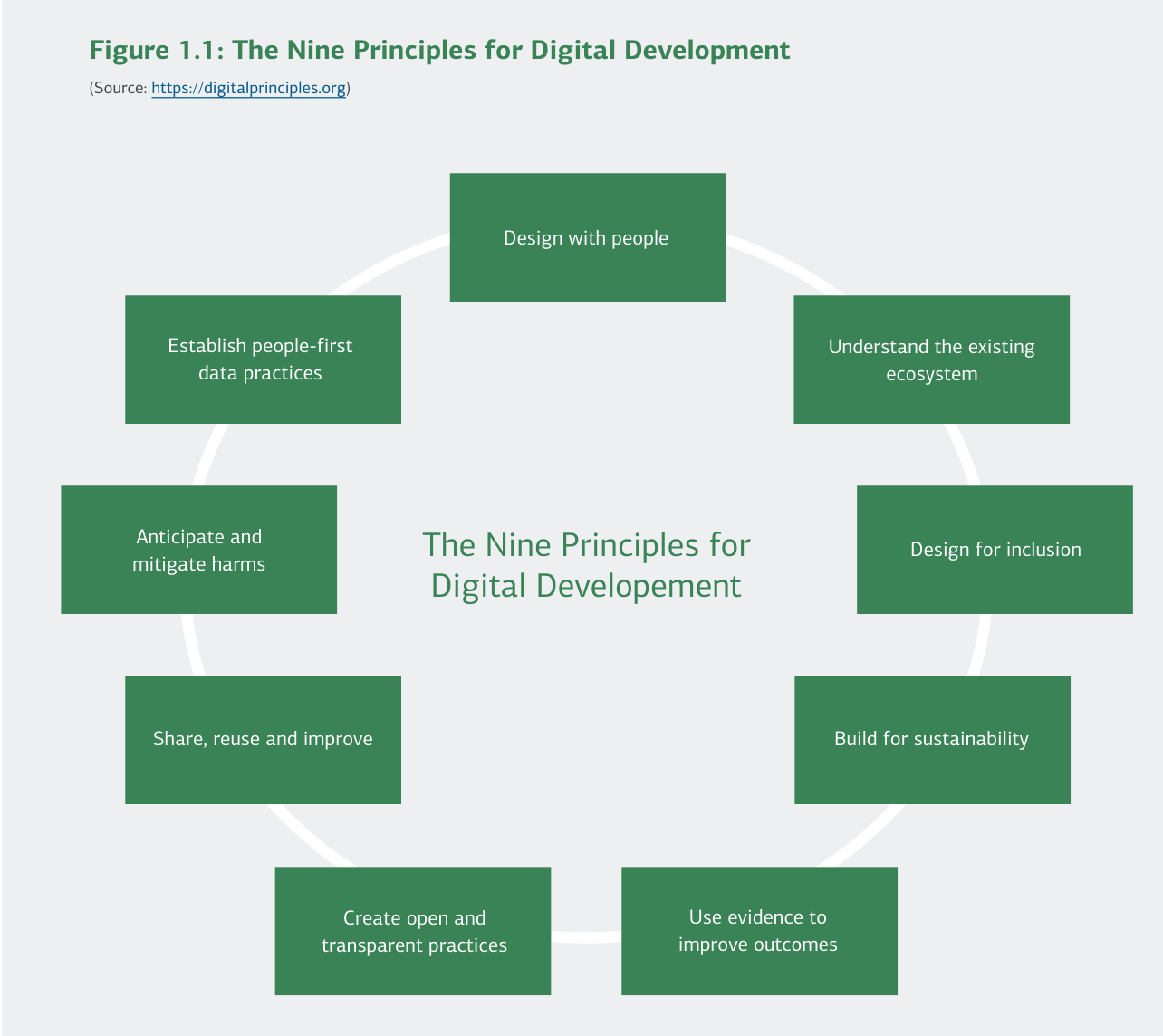

Digital transformation does not only impact the personal space but also influences and changes social and economic development processes, making them more efficient, more sustainable, and faster. It can also aid in structuring them more democratically, allowing for participation and co-creation. Because of the transforming nature of digital elements in development cooperation, KfW has endorsed the Principles for Digital Development established by the Digital Impact Alliance (DIAL) of the UN Foundation. The nine principles are international best practices, which are created as a set of living guidelines for planning and implementing effective, efficient, and sustainable digital approaches in development projects. > Digital Principles

The Nine Principles for Digital Development are:

-

Design with people: Good design starts and ends with people that will manage, use, and ideally benefit from a given digital initiative. To design with people means to invite those who will use or be affected by a given technology policy, solution, or system to lead or participate in the design of those initiatives. Those who ideally benefit from the initiative and those who will maintain/administer the initiative need to participate and engage in the initial design phase and in subsequent iterations Meaningful participation means to create opportunities for people to innovate on top of products and services; to establish avenues for feedback and redressal that are regularly monitored and addressed; and to commit to agile methods that allow for continual improvement. See Section 2.1 Institutional Approaches and Digital Rights Check.

-

Understand the existing ecosystem: Digital ecosystems are defined by the culture, gender and social norms, political environment, economy, technology infrastructure and other factors that can affect an individual's ability to access and use a technology or to participate in an initiative. Understanding the existing ecosystem can help determine if and how we should engage, as ecosystems can have both positive and negative dynamics. Through this understanding, initiatives should adapt, to the extent appropriate, existing technology, and local actors. This includes understanding existing government policies, sector policies, and efforts to expand digital public infrastructure. This also includes understanding existing access to devices, connectivity, affordability, digital literacy, and capacity strengthening opportunities so that initiatives are designed to accommodate or strengthen these realities. See Section 3.1 Project Preparation.

-

Design for inclusion: Digital initiatives can drive social progress by dismantling systemic barriers related to gender, disability, income, geography, and other factors. Technology initiatives should be designed to be accessible and usable for a diverse range of people, including those with disabilities, low digital literacy, those who speak different languages, who face obstacles to device access/affordability/connectivity, and those from different cultural backgrounds. This can be achieved by adopting iterative, agile methodologies and by leveraging redressal systems to quickly identify - and address - challenges that negatively impact certain groups of people including those who are not online. See Section 3.1 Project Preparation and Digital Rights Check.

-

Build for sustainability: Build for the long-term by intentionally addressing financial, operational, and ecological sustainability. Building for sustainability means presenting the long-term cost of ownership-both technology licenses, operations and maintenance, capacity building, etc. Ecological sustainability requires considering an initiative, solution, or system's potential to help people and communities adapt to the changing climate. At the same time, they should seek to minimize the environmental impact of any initiative, solution, or system, particularly the CO2 emissions generated by any hardware or software during the entire lifecycle. Building for sustainability does not mean that all products, services, or policies will last forever. Optimizing for sustainability may result in consolidating services, transferring knowledge, software, and/or hardware to a new initiative, planning for the secure transfer (or deletion) of data at the end of a project,or helping clients to transition to a new, more relevant product or service. See Annex 2 Tool Type Fact Sheets.

-

Use evidence to improve outcomes: Evidence drives impact: continually gather, analyze and use feedback. Over time, good practices in understanding monitoring and evaluation of technology initiatives have evolved to emphasize outcomes on people and communities, rather than just access and usage. To understand outcomes for people and communities, it is necessary to use a variety of methods - both technology-enabled and analogue - to gather, analyze, and use feedback to get a holistic view of the impact of technology on people and communities. This also includes providing redressal channels for people to submit feedback and complaints, which are regularly monitored, addressed, and analyzed. Involve people in the design and implementation of the monitoring and measuring of outcomes as well, so that the outcomes being measured are relevant and meaningful to them. See Section 2.2.3 The Use of Data Sources.

-

Create open and transparent practices: Effective digital initiatives establish confidence and good governance through measures that promote open innovation and collaboration. Open and transparent practices can include but are not limited to: clear and accountable governance structures that define roles and responsibilities; open and proactive communication, decisions, policies, and practices; mechanisms that allow stakeholders to provide feedback, ask questions, and raise concerns; and quick and transparent responses to feedback. In terms of technical design, they can include the use of open standards, open data, open source, and open innovation. When organizations do not prioritize transparency and openness, it results in a lack of trust. Trust is critical to encourage participation, and without it, people will rationally choose to avoid the risks associated with engaging with digital services and sharing their data - thus foregoing any potential benefits. See Section 2.2.2 on Open-Source as well as Section 2.2.4 on Open Data and > the RMMV Guidebook repository on Github.

-

Share, reuse, and improve: Build on what works, improve what works, and share so that others can do the same. Avoid innovation for the sake of innovation. By sharing, reusing, and improving existing initiatives, we pool our collective resources and expertise, and avoid costly duplication and fragmentation. Ideally, this collaboration leads to streamlined services for people. This requires organized and accessible documentation, and is greatly facilitated by adopting open standards, building for interoperability and extensibility; using open source software; and contributing to open source communities. Following this principle can save time and money and lead to better products and servicest. See Section 2.2.2 on Open-Source as well as Section 2.2.4 on Open Data and Annex 2 Tool Type Fact Sheets and > the RMMV Guidebook repository on Github.

-

Anticipate and mitigate harms: To avoid negative outcomes from any given digital initiative, plan for the worst while working to create the best outcomes. Examples of harms include enabling digital repression (including illegal surveillance and censorship); exacerbating existing digital divides; technology-facilitated gender-based violence; undermining local civil society and private sector companies; amplifying existing, harmful, social norms; and creating new inequities. These harms are particularly relevant, and the impacts are less known, when it comes to machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI). Harm mitigation is context-specific, and requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates technical, regulatory, policy, and institutional safeguards. Without these types of safeguards, specific groups of people may decide to disengage or systems may be used to intentionally target certain groups of people, undermining all sustainable development goals. See Section 2.3 Legal and Regulatory Conditions and Recommendations and Digital Rights Check.

-

Establish people-first data practices: People-first data practices prioritize transparency, consent, and redressal while allowing people and communities to retain control of and derive value from their own data. This principle emphasizes the need to avoid collecting data that is used to create value (financial or otherwise) for a company or organization, without delivering any direct value back to those people from whom the data is derived. It is thus critical to put people's rights and needs first when collecting, sharing, analyzing, or deleting data. In this context, 'people' includes those who directly interact with a given service, those whose data was obtained through partners, and those whose are impacted by nonpersonal datasets (such as geospatial data.) When collecting data, it is important to consider and follow relevant data standards and guidelines set at the international, regional, national, or local level. Digital initiatives should obtain explicit and informed consent from people before collecting, using, or sharing their data;and consider to invest in people's capacity to navigate the tools, redressal systems, and data practices. People-first data practices also include sharing data back with people, to use this data as they see fit, and providing access to individual, secure data histories that people can easily move from one service provider to the next, wherever this is feasible.See Section 2.3 Legal and Regulatory Conditions and Recommendations and Digital Rights Check.

With the endorsement of the Principles for Digital Development, KfW emphasizes the importance of digital solutions in development projects and as an important means of reaching the development bank’s goals. The aim is to integrate the principles within the organization as well as in the approaches, policies, and processes guiding all development activities.

These digital principles assist in choosing the right procedures and structures for the specific project context, especially in the detailed planning of such tools within development projects and within a selected RMMV approach. The principles can be applied in all areas of RMMV and along with all institutional approaches and technical tools. However, it is important to emphasize that the principles are heavily context-dependent and cannot always be applied simultaneously, since there can be certain trade-offs that have to be weighed up for the specific context.

In line with the above principles, the Danish Institute for Human Rights and GIZ have developed a “Digital Rights Check” to help identifying human rights risks when designing and implementing digital tools or solutions within international development cooperation projects > Digital Rights Check.

1.5 Limitations and Risks of RMMV

Although RMMV employs a multitude of well-developed approaches and tools, accessibility challenges limit KfW’s influence on projects and its ability to mitigate risks in time. These challenges, together with project complexity and governance issues, may mean that the use of RMMV is not sufficient for successful project implementation. At times, some risks can only be partially mitigated and need to be accepted by KfW and BMZ. Overall, the use of RMMV can also imply that KfW’s reputational risks are increased.

Trust is crucial for the implementation of all KfW projects—including projects that are remotely managed, monitored, and/or verified. The challenge is that trust is usually created through frequent in-person interactions, reliable monitoring, and transparent reporting. Therefore, the chosen RMMV approach should ensure that this trust can be developed despite the increased remoteness between stakeholders by assuring sufficient in-person interaction between national KfW staff and the PEA or regular videoconferences between the KfW PM, the PEA, target groups, and representatives, and/or other relevant stakeholders, for example. This can help considerably in building trust and improving collaboration among all project parties.

Limitations

Wherever possible, RMMV tools should be used to complement on-site verification and personal exchange with the partners and the main stakeholders on the ground. Remote communication bears the risk of misinterpretations and the development of trust amongst stakeholders remains a challenge.

There are changes in situations due to which a planned or ongoing project may have to be suspended or closed if no feasible RMMV approaches and tools are available to overcome the sudden challenges and mitigate the respective risks. Some examples: Complex projects that require continuous or frequent onsite international expertise may not be deliverable through RMMV. For instance, works that require a very specific skillset that might only be available through international experts/consultant staff being onsite during construction. Such projects should be avoided if travel for international staff is not possible.

- Projects with high environmental and social risks, and/or projects for which sufficient environmental and social data to inform decision-making cannot be collected in a timely or reliable manner.

- Projects in regions that cannot even be accessed by non-resident PEA or local consultant staff must be avoided. While technologies can facilitate even some data collection from areas that cannot be accessed in person, this is not sufficient to deliver FC projects.

- Projects that require direct involvement of target groups in RMMV should not be implemented in countries/ regions that have a significant lack of freedom of expression (freedom of speech, opinion, the press) if this risk cannot be sufficiently mitigated within the project design, since the social risk would be too high that an individual becomes negatively affected by his/her participation or feedback, which would be unacceptable for KfW.

- Projects in areas where the government does not allow any independent data collection and the use of electronic data collection devices, such as smartphones, by any non-residents. This may prevent RMMV approaches crucial for verification from being carried out, thus rendering remotely managed projects not implementable.

- PEAs that do not share data or allow external data collection may not be suitable partners for remotely managed projects. A PEA’s refusal to share the data that KfW may require for their verification or a lack of support for additional information gathering by third parties may make RMMV approaches impossible. Therefore, PEAs must be willing to cooperate on these issues. Since FC funds cannot bereprogrammed, this condition may have to be addressed during intergovernmental negotiations; see Section 3.1.1 Government Negotiations.

Risks

Project Implementation and Monitoring Risks Increased risk of corruption.

In many cases, RMMV approaches cannot fully replace visits of international staff that are crucial to prevent and detect corruption.

Access to project sites by local or national staff may deteriorate during the implementation of the project.

Even if national staff replace international staff for site visits, it must be recognized that their access is not continuous. Frequently, staff or consultants may overstate accessibility to certain sites to win a contract. Furthermore, they may underestimate that access conditions may change frequently. If this happens, it may be the case that project sites are completely shut off from RMMV.

Limitations in monitoring affect program quality.

The national staff that take over the monitoring responsibility may not have the expertise of international staff typically responsible for monitoring. Regular site supervision and other quality assurance mechanisms may be more difficult to implement, thus leading to lower quality outcomes.

Capacity challenges may be difficult to recognize and respond to.

If international staff cannot access project sites, some staff capacity deficits may be difficult to recognize. Furthermore, on-the-job training and other tangible capacity-building measures built into the project may be limited if they cannot take place in the real-life context of project site visits.

Technological equipment used for RMMV has a high value, thus making it prone to theft.

This should be considered when setting up such equipment. For instance, it may be possible to install equipment at less obvious locations (e.g., integrate a water sensor into a bridge) or to have equipment guarded by security staff on construction sites.

The potential leaking, theft, or disappearance of projectmonitoring information might hamper project progress or impact and additionally pose security risks

to project stakeholders and project-affected people, in particular if this involves personal data. This risk needs to be mitigated through appropriate privacy, data protection, and data security procedures and provisions; see Section 2.3 Legal and Regulatory Conditions and Recommendations.

The quality of monitoring and data may deteriorate. RMMV makes it more difficult to gather qualitative information. Overall, information standards may be lower if triangulation is lacking, and international staff cannot make targeted visits to improve and/or verify information quality. Furthermore, there is a danger of gathering too much data that cannot be analyzed and interpreted in an appropriate timeframe or too little data (e.g., not asking an important follow-up question about a problem encountered) or the wrong data (e.g., interviewing only household heads, i.e., men, about food security matters).

- Lack of triangulation may erode trust between the KfW PM and the PEA. In an RMMV setting, it is more difficult for KfW staff to triangulate information received from the PEA and other stakeholders. This lack of triangulation may erode trust in the PEA even if the PEA reports correctly. Using a coherent mix of RMMV approaches and continuous triangulation can help mitigate this problem.

- If the PEA or Implementation Consultant does not report correctly and Remote Verification does not manage to pick up on it, there is a risk of information/data being falsified, potentially resulting in corruption, harm, and failure of the project.

- There is a risk of relying too much and too long on already established RMMV systems and tools to economize efforts in conducting physical on-site progress reviews, so that KfW management or staff might be tempted to conduct their field missions less frequently, even though the trips would, in principle, be possible. This may result in increased corruption and do-no-harm risks.

Trust may further be eroded by communication difficulties. Although information and communication technologies go a long way towards improving communication, it may not be possible to replace regular face-to-face communication. Some local stakeholders face language barriers, are not used to virtual communication, or take it less seriously. In other cases, videoconferences or calls with many different stakeholders may lack balanced moderation/chairing. If this is the case, it may cause frustration on all sides, or even a lack of trust between KfW, the PEA, and the other stakeholders.

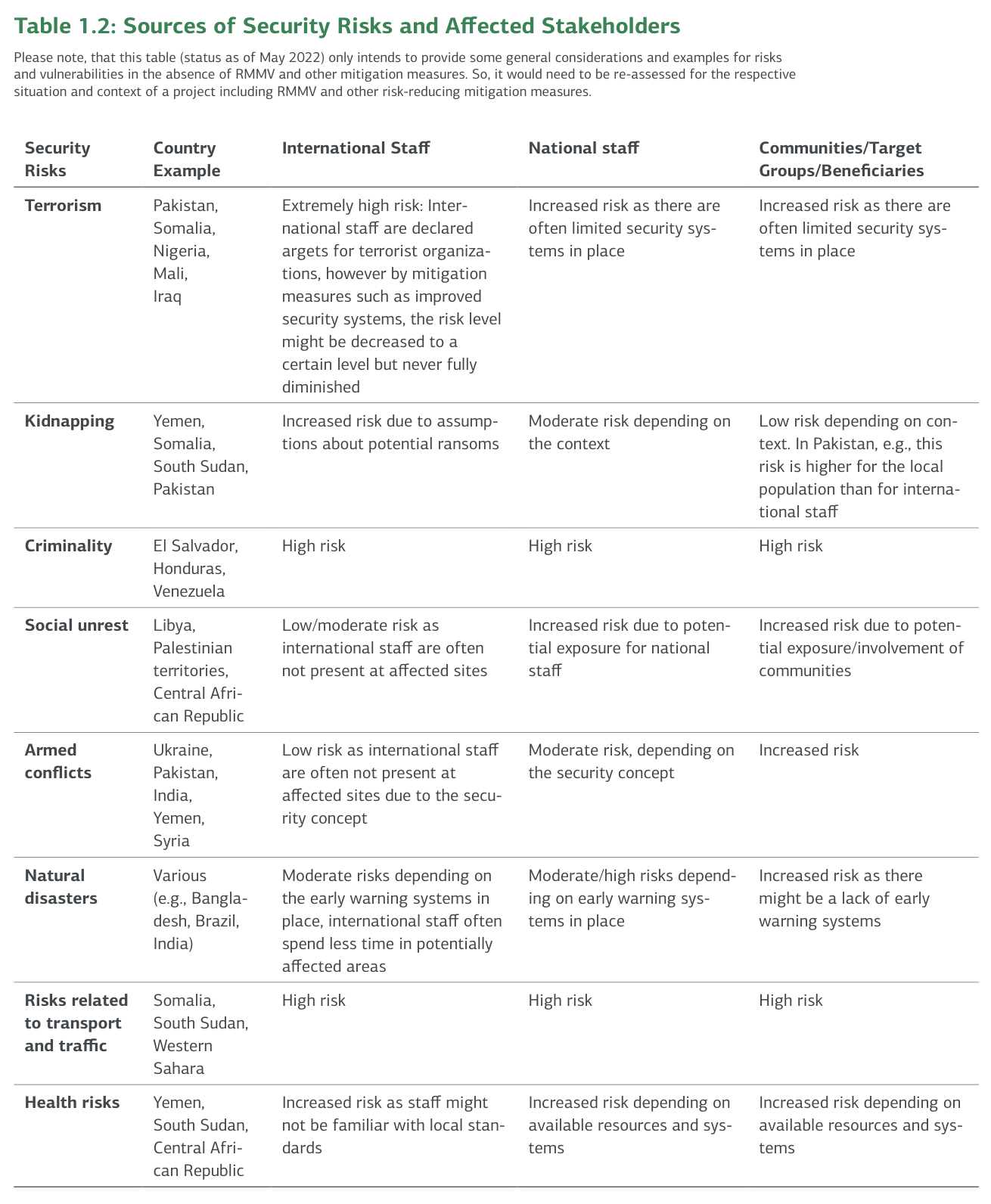

Do-No-Harm Risks

Projects that rely exclusively on an RMMV approach are at a higher risk of not reaching the intended target group or all project–affected persons (PAP) or favoring parts of the target group over others. The lack of international staff presence may increase pressure and social and political expectations on national staff. In a context where family, tribal, ethnic, and political affiliations are strong and chronic poverty is high, local and national staff may be susceptible to pressure to provide assistance to certain groups or to favor certain suppliers. Furthermore, authoritarian governments that discriminate against specific target groups may be freer to do so if international staff are not present. Perceived or real favoritism in targeting project beneficiaries, contractors, and suppliers is a potentially damaging outcome in this case. If the views of target groups are not sufficiently incorporated into project committees, projects may suffer. When considering local communities, remotely managed projects commonly rely on local committees that are usually composed of local representatives. Consequently, the views and opinions of women and vulnerable population groups may systematically be overlooked. On a more general level, RMMV approaches may be prone to focusing on the technical aspects of collecting information, especially in terms of project progress, while neglecting “softer” aspects that are very relevant to the target groups.Security threats and risks to personnel and/or communities RMMV approaches may imply a shift of risk from international staff to national staff. A central question is whether national staff always face the same vulnerabilities as international staff. Frequently, consultants or partner organizations may not have the same security and risk management systems in place for national staff. shows, however, that many of the typical risks that lead to the application of RMMV approaches also affect national staff and target groups:

Table 1.2: Sources of Security Risks and Affected Stakeholders

Please note, that this table (status as of May 2022) only intends to provide some general considerations and examples for risks and vulnerabilities in the absence of RMMV and other mitigation measures. So, it would need to be re-assessed for the respective situation and context of a project including RMMV and other risk-reducing mitigation measures.